Earlier this year, a cardiac catheterisation procedure had to be halted when the monitor PC of a Merge Hemo diagnostic system went black.

The official report suggests that the surgery at a US hospital was delayed for five minutes "while the patient was sedated so that the application could be rebooted." The reason being that anti-malware software was performing hourly scans on the device.

Was this a case of the Internet of Medical Things getting it wrong and potentially putting a life at risk? Nope, the US Food and Drugs Administration says "the cause for the reported event was due to the customer not following instructions concerning the installation of anti-virus software."

In other words, human error.

(Don’t just) buy more bullets

This serves to illustrate how even relatively secure technology can fail to deliver when the human factor is taken into account.

You have a device that comes with security guidelines that quite clearly recommend anti-virus software be configured so "it does not affect clinical performance and uptime while still being effective.”

This device continues to suggest it should "scan only the potentially vulnerable files on the system, while skipping the medical images and patient data files." Yet all of that can be ignored, and the consequences are scary.

As scary as people with their hands on the NHS purse-strings who consider that security is a product. Back in the year 2000, veteran security guru Bruce Schneier said "security is a process, not a product." He was right then, and he is right now.

You cannot secure your data just by buying into a technology. You need to buy into a culture of secure thinking as well. And that means making sure that staff, from the very top down, are all properly educated to understand both risk and how to mitigate it.

Yet how many organisations, and NHS trusts are just as guilty of this as anyone, rely upon security silver bullets? Worse still, having missed the target with one silver bullet they reload and fire another in the firm belief that it will surely save them?

Think human policies and procedures

Of course, I'm not saying that all security problems can be traced back to human failure, and I would include flawed procedures, processes and policy within that statement.

Policies are the guidelines that drive both process and procedure: they answer the 'what do I need to know?' question.

Process can be thought of as the big picture, while procedure is the more detailed view that brings the 'how do I do that?' answers into play.

The human factor determines whether all of these are effective in mitigating risk, or just introducing additional risk into the threatscape.

I guess what I am saying is that all too often education – awareness training if you will – is negotiated out of the cost of security. Heck, the budget is limited enough, so why waste it on risk awareness when you can just buy more bullets?

I'm not even going to get into the fact that people still end up buying the wrong bullets, and the wrong guns to fire them, then aim them in the wrong direction. That can wait for another column…

Training in security

The Proofpoint Human Factor Report 2016 observed that across 2015 attackers increasingly infected computers by tricking people into doing it themselves rather than using automated exploit technology.

This can be evidenced by the fact that more than 99 per cent of documents used in attachment-based malicious threats relied upon human interaction to execute the payload. Social engineering, exploiting the human attack surface in order to gain access to data or networks, is not only a growing threat it's also one to which healthcare is particularly vulnerable.

Why so? Just think about it: health is a caring profession in which the focus is on saving lives. Sharing data is just an inherent part of that.

Staff are trained not to keep the bad guys out, but to ensure the timely application of treatments and maintain an infrastructure to deliver the same. With a relatively low investment when it comes to cyber security – and some might argue an equally low concern for it in the overall scheme of things – health has become a very attractive target for the bad guys.

So understanding the importance of basic human error – be that down to ignorance, negligence or somewhere between the two – must sit front and centre of any security strategy.

It seems to me that even those trusts that would argue that they are educating their staff are not providing training and awareness that is effective enough.

Until there is a culture of security just as there is a culture of care within the NHS, then we will continue to read about data loss, system breaches and security that just isn't good enough.

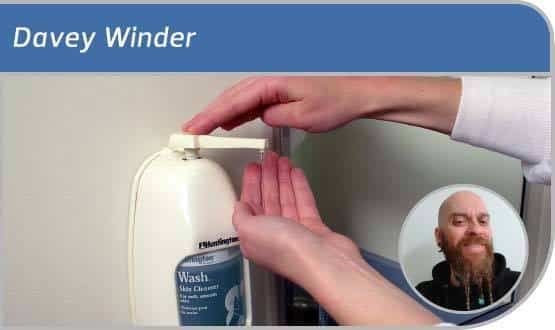

Cyber security handwash?

Here's a thought to end with: what if clicking an unsolicited link or opening an emailed attachment was considered as potentially dangerous, in the security sense, as not washing your hands as you enter or leave a ward?

The hand wash analogy seems like a good one to me, as it has reduced infection rates both cheaply and effectively just by making everyone aware of how such a simple action can reduce risk.

Davey Winder

| ||||