“Whatever, in the course of my practice, I may see or hear – even when not invited – whatever I may happen to obtain knowledge of, if it be not proper to repeat it, I will keep sacred and secret within my own heart.” Hippocratic Oath 500 BC

The notion that doctors should keep the information they receive from patients “sacred in their own hearts” goes back 2,500 years.

As a medical student in the 1970s it was drummed into me: Sharing confidential information with medical and nursing colleagues was acceptable if it directly related to the care of the patient. However, it was not my job to include personal matters shared with me as a GP in referral letters, unless it was directly relevant to the care in hand.

Similarly, sharing information with wider colleagues including allied professionals and social workers was – without exception – something in which any benefit to care had to be carefully weighed against the breach of confidentiality involved.

Risks and costs

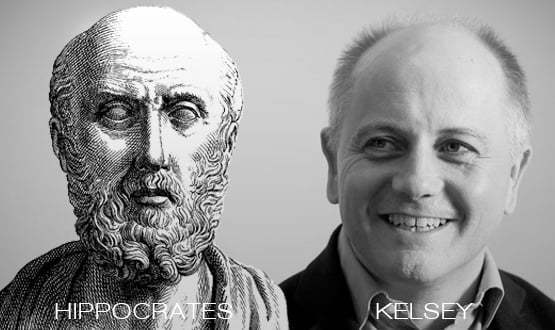

Both confidentiality and information sharing are 'good'. Hippocrates and Tim Kelsey, the director of patients and information at NHS England, and the most vigorous and articulate proponent of seamless clinical data around at the moment, are both speaking to big, important, principles.

But today’s excitement over integrating care and the promise of big data means that confidentiality is less honoured. This carelessness is less than ten years old.

What has changed is that while the risks of breaking confidentiality have stayed constant, the costs of routinely sharing information via interoperable platforms are falling dramatically. Consequently, we tend to look more benignly on arguments for sharing information than we used to do.

This matters because confidentiality isn’t primarily transactional. It is about the trust (its Latin origin confidere means ‘to trust fully’). This trust lies at the heart of the clinical encounter – break it and you will have nothing.

It is created by the act of me telling you, the clinician, information that makes me, the patient, vulnerable: how my marriage is breaking up; how I drink too much; that I am afraid of dying; or that my father abused me for 12 years.

Sharing this level of information always takes courage. As a GP listening to these deep, gasping truths emerge in a consultation I felt I was witness to an unfolding succession of gifts, confessions, tragedies.

Confidentiality – “holding this painfully revealed information sacred in my heart” – is the homage that the professional pays to the patient’s struggle and to their courage. Treating confidentiality simply as a transactional issue that can be toggled on or off (“can I just access your Summary Care Record?”) not only does violence to the patient’s courage, it diminishes the professional’s sense of themselves.

Helping to square the circle

So is it possible to square this circle? Can we have the manifest advantages of shared clinical information whilst staying true to the deep Hippocratic need for boundaries?

Or, to put it another way, how can we structure the Summary Care Record to reinforce rather than weaken confidentiality? Some of the wish list might include:

- Patients would be able to see how their record looked to different staff – click ‘receptionist view’, for example, and you would see that they can see medications but not clinical diagnoses or free text comments.

- The electronic patient record would automatically email or text patients when someone had viewed their record – ‘Mary Smith, medical secretary viewed the highlighted parts of your record at 14.15 on 12/12/14’ – (a version of this seems to be under discussion).

- When accessing a record for an unusual reason, staff could be shown a screen shot of their own record with the caption: “This is your record. Would you agree to it being viewed in these circumstances?”

- To help clinicians, all patient annotations would be colour coded.

- The ‘sealed envelope’ facility is currently used to hide major diagnoses that patients do not want shared. But there is much information gathered by GPs, mental health and STD professionals that patients might want shared with some professionals but not others. We should consider redesigning the sealed envelope facility as a series of speciality-specific views of the SCR.

Software always incorporates the values of those building it. If Hippocrates was a geek, then perhaps these are the kind of things that he might ensure were valued in the SCR.

Baking old thinking into new IT

All this is even more important because we live in a culture where sharing personal information via social media is the norm, and where celebrities are eager to let slip salacious titbits to feed their online personas.

This low friction world can make confidentiality seem passé. It would be understandable if those building the SCR thought that confidentiality was pretty much synonymous with tweaking your privacy settings on Facebook.

It isn’t. Confidentiality and the truths that can be disclosed within it lie at the heart of medicine and of healing.

Behaviours do not endure for 2,500 years without good reason. The information held on our electronic health records is indeed “secret and sacred”.

Writing the code that allows us to share it appropriately requires a deep respect that goes way beyond the binary toggle of ‘consent on’/’consent off’.

Software, well executed, has a tremendous ability to deliver that Holy Grail of 'changing the culture' – just look at how we all now interact with Facebook or use online banking. It would be a tragedy if we inadvertently threw out the 2,500 year old Hippocratic baby with the ‘seamless’ bath water of the SCR.

Paul Hodgkin

Paul Hodgkin is founder and chair of Patient Opinion, a website on which patients, service users, carers and staff can share their stories of care across the UK. Patient Opinion is a not-for-profit social enterprise based in Sheffield.

Until 2011, Paul also worked as a GP and has published widely including in the BMJ, British Journal of General Practice and the Guardian and the Independent. Follow him on Twitter @paulhodgkin.