“I saw a need for something to address the basic psychomotor skill of moving the table and moving the equipment,” he says.

“I thought: ‘There has to be a better way of doing this than learning on the job, on real patients, using radiation, when there are so many simulators around. When you think of games like Tomb Raider, they provide a learning element, so why not transfer that to something real?’”

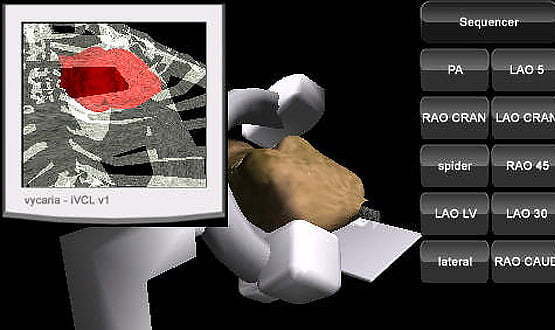

After developing a version for PC in 2003, Larson returned to the idea a few years later, and Virtual Cath Lab was launched as a mobile app in 2011. It has now been downloaded 10,000 times from Apple’s app store, in countries as far away as Vietnam and Mexico, as well as the UK.

Feedback has been positive, says Larson. “It delivers the basics. It gets you to the stage where you can operate the real equipment, and look at the anatomy with some intelligence, and hit the ground running.”

Few apps are diagnostic

The use of mobile apps is becoming increasingly common – about 1,000 new healthcare apps are released every month (although some are aimed at patients, rather than at doctors and other clinicians).

A small subset of these relate to imaging. Earlier this year, Dr Mark Rodrigues, a radiology registrar at the Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh, published with colleagues a study in ‘Insights into Imaging’ that identified 321 imaging smartphone apps that are currently on the market.

Of these, the biggest group (158) were designed for ‘teaching’ purposes, and include flashcards, questions, revision guides or notes, textbooks, cases, tutorials and talks.

Teaching apps can be immensely useful for students, says Rodrigues. “If it’s a downloadable app, you can use it where there’s no internet access, so it’s made it easier to publish teaching materials.”

After that come ‘reference’ apps (96 in all), which include guidelines, cancer staging, radiology positioning guides, scanning protocols, glossaries, calculators (including radiation dose calculators), converters and cost comparisons.

The third biggest group consists of the 29 DICOM-based ‘viewing’ apps. Many of these are produced by corporate IT vendors – most manufacturers of picture archiving and communications systems have smartphone or iPad versions of their product.

Only three of these viewing apps had US Food and Drug Administration clearance for primary diagnosis, while 62% explicitly stated they should not be used for primary diagnosis.

Generally, says, Rodrigues, viewing apps are not designed to be diagnostic. “I think the main emphasis is either to use them in consultations – to show a scan to a patient – or to remotely manage an MRI list.

“A radiographer could say: ‘We’ve done the first few sequences of this patient, can you have a quick look at them, and do we need to do anything else?’ For that you don’t need such great resolution.”

Although smartphone screens are generally too small to allow for diagnosis, some academic papers have looked at the accuracy of images on tablets, says Rodrigues.

“Most of them are encouraging in that they didn’t find any significant difference between people who looked at the images on tablets in comparison to those who looked at them on proper workstations.”

Nonetheless, hospitals that implement viewing apps on tablets will want to put rules in place governing how they should be used.

Not all apps are created equal

Although some medical apps provide obvious benefits – such as being able to look up information while on a ward round or to study for an exam while on the train – there are also risks.

Ewan Davis, founder of the Healthcare App Network for Development and Innovation, says: “There are lots of apps that are poor quality or inappropriate, and sometimes that inappropriateness is about globalisation.

“There are American apps that are perfectly fine in the US, but you really wouldn’t want to use them in the UK, because of things like units and different drug names, and because they have ways into the system that don’t make sense in an NHS context.”

Lack of interoperability is also a limitation, says Davis. “One of the features of an app is that it does a very limited range of things very well, so you end up as a user with lots of apps, such as the bedside monitoring app, the prescribing app, a PACS app.

“They all do their job excellently, but they don’t work together. If you want to look at an image in relation to a particular patient, you may then want to prescribe for that patient, and you may want to record some observations about that patient.

“Before you know it, you find that you’re having to re-enter the same data three times, or doing some sludgy copying and pasting.”

Many mobile apps reside on the user’s phone, but imaging apps are likely to be connected to hospital networks.

“Anything which transmits any patient-identifiable information is a slight concern,” says Rodrigues. Security protocols would need to be put in place, particularly if hospitals allow clinicians to use their own mobile devices to access the network.

Regulation is a work in progress

So far, regulation of mobile apps has lagged behind development, and there have been worrying instances of faulty apps providing inaccurate drug dose calculations.

The FDA has now issued guidance saying that it will regulate those medical apps that “transform a mobile platform into a regulated medical device” and could pose a risk to patients if they “do not work as intended.”

Specifically, it refers to mobile apps that “transform the mobile platform into a regulated medical device by using attachments, display screens, or sensors or by including functionalities similar to those of currently regulated medical devices.”

The guidance has implications for UK developers wanting to market their apps in the US. In Europe, apps that are regarded as ‘medical devices’ are regulated by the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency, but the regulations are currently being updated.

NHS England has two clinical safety standards (DSCN 14/2009, which is aimed at manufacturers of health software, and DSCN 18/2009, which is aimed at those deploying and using health software) that mandate compliance if they are deemed to be within the scope of the standards.

“We are working up a process that applies the principles of the manufacturer standard to those health apps that are not medical devices,” says Maureen Baker, clinical director of patient safety at the Health and Social Care Information Centre, adding that the approach will be “light touch yet robust.”

There are also technical hurdles to overcome. While information and teaching apps proliferate, interactive apps such as Virtual Cath Lab are still rare.

This, says Larson, is partly because of the limitations of Apple’s requirements relating to usability and interface design, and partly because it’s challenging to create interactive games that are small enough to download easily but have enough detail to be useful.

Regulatory, security and technical barriers have to be addressed before mobile apps become an everyday part of the radiologist’s toolkit. The pace of technological development, however, means that there is plenty of untapped potential.

Some of the most exciting opportunities will come with augmented reality – Larson’s company, Vycaria, is already working on an AR app that will enable users to see how a particular product (such as a catheter) works inside an anatomical model of the heart, for example.

Eventually, perhaps, the limitations of smartphones will see them replaced by wearable augmented reality products, such as Google Glass, which can potentially feed doctors live data while performing a procedure.

Live panel: HANDI Healthcare Apps will be at EHI Live 2013, and discussing issues around the safety and regulation of apps. Dr Maureen Baker will also be presenting on safety, standards and safety cases. The UK Imaging Informatics Group will be holding its annual meeting alongside the conference and exhibition, which takes place next week.

EHI Live 2013 is more than a meeting, more than an exhibition. For anyone involved in the use of information in healthcare it’s a golden opportunity to update knowledge, get answers to questions, meet the experts and think about the future. This year’s conference is free for all visitors to attend.