Surgeons at Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust are using Microsoft’s “mixed reality” headset to look inside patients before they operate on them, in an effort to make procedures safer and more time-efficient.

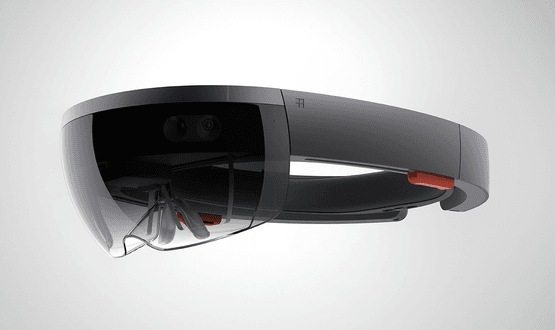

HoloLens, which combines elements of virtual reality (VR) and augmented reality (AR), enables surgeons to map the anatomy of a patient and overlay 3D images on top of their limbs so they can see blood vessels, bone and muscle before making an incision.

The functionality has been achieved by uploading CT scans of the patient into the Microsoft HoloLens, which can then be projected on top of the patient before the surgery begins. This allows surgeons to “see” each patient’s unique anatomy and plan operations accordingly.

Other surgeons in the operating room who are also wearing a headset can view the procedure through the eyes of their colleagues, making collaboration easier.

Dr Philip Pratt, a research fellow in the department of surgery and cancer at Imperial College London, said: “To perform the best operation, you have to plan it meticulously beforehand. This technology allows us to experience the data that we have collected from patients before their operation in the most realistic and natural way.

“You look at the leg and essentially see inside of it; you see the bones and the course of the blood vessels.”

According to Microsoft, the technique has been used to operate on a 41-year-old man who had injured his leg in a car crash, as well as an 85-year-old woman who had broken her leg.

For both procedures, surgeons at St Mary’s hospital used HoloLens to guide them in moving blood vessels from one part of the body to another in order to heal wounds.

This is often done in a case where a patient suffers an open wound and requires reconstructive surgery. In such incidences, skin and blood vessels are taken from an undamaged part of the body and grafted onto the wound, allowing it to close over and heal.

It was proposed that the technology could be used as a replacement to traditional handheld ultrasound scanners, which find blood vessels by detecting blood flow under the skin.

James Kinross, a consultant surgeon at St Mary’s Hospital, pointed out that this is a more time-consuming method that also required a degree of guesswork.

“You don’t want to make an incision and find out that you should be two centimetres over here, because that might compromise the operation. This is all about best outcome for the patient,” said Kinross.

The researchers are now looking to extend the trials to more patients and hospital and are examining where else the technology could be applied to the clinical environment.

VR and AR are increasingly gaining interest from the medical field, with proposed applications ranging from education and training to tools for rehabilitation, pain management and treating depression.

Last October, a team of surgeons from Mumbai and London used HoloLens to collaborate on surgery being carried out on a patient at Royal London Hospital.

14 February 2018 @ 16:26

This is more AR and it is like any digital technology, 1) get over the hype, 2)get a clear understanding of where it will add value/enable a better care model, 3) get clinical buy in based on the better outcomes for patients and 4), implement it into a new care model as business as usual. VR has its place as well, I would not write any of this off.

14 February 2018 @ 07:02

Hang on, according to Christine walters CIO Interview VR is the most over rate technology and and the technology needs researching and trialling to provide the evidence that it will work. And yet here, Imperial are using the technology on patients. Although it says can be improved, I’d suggest the patient outcomes would demonstrate the evidence. Well done Imperial for progressing this.