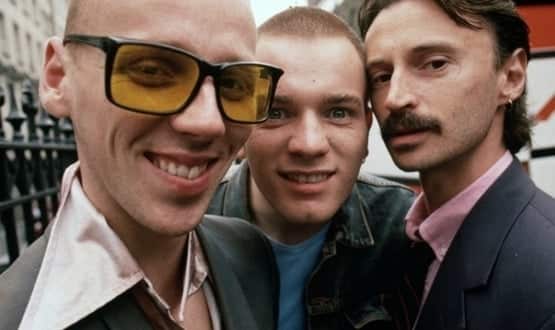

The return of Trainspotting to our screens means the slogan of Generation X, ‘Choose Life’, is once again on the lips of the nation. Ian Pocock, director of health at Transform, says we need to take note if we are to save the health service.

When Katharine Hamnett told a nation to Choose Life forty-three years ago, she spoke to a generation.

It accompanied them through childhood and into adulthood, as it morphed from the clean-cut image of Wham into the heroin-fuelled words of Renton running through the streets of Edinburgh in Trainspotting.

Twenty years later the message is loud and clear as once again Renton, Sickboy, Spud and Begbie wreak havoc, and the original intent has never been more relevant.

The trouble is too many of us choose not to choose life. Instead we, to quote Renton (carefully), sit on that couch watching mind-numbing spirit-crushing game shows, stuffing junk food into our mouths. Add to that our smoking and drinking habits and you have the perfect storm rocking NHS’s very foundations.

Prevention now literally better than cure

Seven out of every £10 the NHS spends on health is on a lifestyle related condition. That amounts to 15 million people in England with at least one long-term condition and 10 million have two or more. This group accounts for 50% of GP appointments, 64% of all hospital outpatients appointments and 70% of all hospital day beds. It is simply unsustainable.

With chances of developing a long-term condition doubling over the age of 45, the Choose Life generation can make a huge impact in solving the crisis. We hold the future of the NHS in our hands, quite literally.

An app a day keeps the doctor away

Modern technology gives us the tools to solve these challenges. But to do this we have to be willing to harness mobile and all it contains in data analytics, messaging, Artificial Intelligence, connected devices and location services.

The Department of Health has long identified that 70-80 per cent of people with long-term conditions can be supported to manage their own condition.

Research by US healthcare giant, Kaiser Permanente supports this. They found that patients with long-term conditions spend just 0.1% of their time in front of a medical professional. This means 99.9% is spent on their own – at home, at work, commuting or in leisure time.

We need healthcare in the 99%, using technology to nudge, support, monitor, to foster behaviour change to prevent ill health, identify emerging health issues and deliver cost-effective interventions. All the time reducing the burden on our healthcare system.

People aren’t ignorant of the effect their lifestyle choices have. It’s finding a way to change habits without it seeming too impossible to even start or becoming an outlier in their community. Just wanting to fit in is one of the biggest hurdles to help people overcome.

To do that we must make the right choices the new norm. This is the essence of our projects for Public Health England.

Digital devices enable users to visualise the unintended consequences of their behaviour. A tracker that stores money not spent on drinking into a pot that would buy an annual holiday is a powerful argument.

Visualising the cubes of sugar in a seemingly harmless yoghurt drink is another. Similar apps are already powerful tools in reducing the UK’s rates of smoking, bolstered by a growing sense that everyone is doing it. Or, in the case of smoking, everyone isn’t doing it.

The keys to those digital interventions will be convenience and inclusion. When one of the biggest reasons for the worsening of a condition is the failure to take the prescribed medication, think of the power of connected devices.

The doctor in my pocket

In a connected world we can put sensors on blister packs, with reminder alerts if they aren’t opened on schedule. The impact of appointment reminders, via text, in the NHS is a 40% reduction in missed appointments.

Often it is simply remembering to do the important things in the midst of our busy lives. Any further problems would motivate their doctor to intervene.

Even when the problem is more deeply rooted than simple forgetfulness, digital has a role to play. Depression medication may treat the symptoms of the illness but not without some unpleasant side effects. To such an extent that many sufferers abandon their treatment.

They will enjoy a brief period symptom free until the core illness resurfaces, bringing them crashing down. But the human brain’s capacity to post-rationalise will diminish the importance of the crash and over-emphasise the brief period of full health. And as a result, the rollercoaster of stopping and starting taking medication continues.

Diary apps have been linked to improving the continued adherence to medication when people realise the impact of not taking their course of treatment.

However, the biggest impact on all of the these conditions is often not to be found in the actual treatment but in the wider life circumstances of the person. Factors like financial situation, exercise, mindfulness, stress, coping skills, nutrition, isolation and education are by far the biggest determinants of health outcomes.

Digital lowers the barriers to entry for people, whether by reducing the stigma attached to having to address their issues, or helping to ‘nudge’ them proactively into new behaviours, or supporting the new choices.

America is leading the way in digital and the UK doesn’t need an injection of private health insurance cash to follow suit. A third of doctors in the US prescribe digital services, ranging from behavioural to medication management.

For those using an app, there is a 10% improvement in people sticking to their drug regime and a 30% improvement in adherence to wellbeing tasks.

Patients in the UK don’t lack motivation to change for the better. What both patients and the NHS do need is the capability and opportunity to Choose Life, and this is entirely within digital’s gift.

Ian Pocock is director of health at Transform, a digital agency which has worked with Public Health England on developing patient education and activation projects.