The government has hardly made a secret of its desire to see patients get online access to their medical records.

The idea has been flagged up in any number of ministerial speeches, and took form in the NHS IT strategy published last May. Indeed, the pledge to give patients online access to their GP-held records by 2015 was one of the few firm pledges in ‘The Power of Information’.

Since then, the commitment has been reiterated in the mandate issued to the NHS Commissioning Board at the end of last year and in the planning guidance that it issued for the NHS in December.

Despite this, an exclusive survey of 1,000 GPs commissioned by eHealth Insider and conducted by doctors.net.uk has found that almost no practices are ready to start delivering on the government’s pledge. More worryingly, it suggests that many have yet to start thinking about it.

A long way to go on access

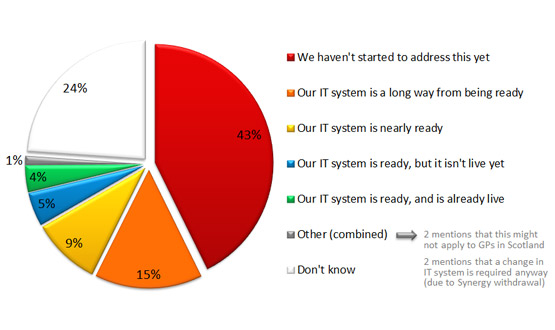

The survey, which was commissioned to explore GP attitudes to patient-facing technology and social media, found that 43% of respondents picked “we haven’t started to address this year” when asked how ready they were to facilitate patient access to records.

A further third said their IT systems still needed work, with 15% of the total sample saying “our IT system is a long way from being ready”, 9% saying it was “nearly” ready, and 5% saying it was ready but “it isn’t live yet.” Just 4% of respondents said “our IT system is ready, and is already live.”

Meanwhile, a quarter (24%) of respondents said that they simply didn’t know how ready their practice was to give patients access to their records.

This pattern of response was consistent across most areas of the UK. Scotland, where there has been no ministerial push on patient records access, had the largest proportion of respondents (53%) likely to say “we haven’t started to address this yet.”

But even in Scotland, 4% of respondents said their practice had a system live. Meanwhile, the old NHS South Central area of England had the smallest proportion of respondents (31%) likely to say they hadn’t made a start.

But in South Central, just 1% of respondents said they had a system that was live; although 6% said their practice had a system that was ready but not live.

See the benefits; don’t like the target

Of course, giving patients electronic access to their records is not just a government imperative. Some pioneering GPs have reported many benefits from doing just that. Probably the best known is Dr Amir Hannan, a GP at Houghton Thornley Medical Centres in Hyde.

Over many years, he has argued that being able to access a shared record helps to build trust and partnership between a clinician and a patient, and being able to see what is written about them encourages patients to take more interest in and responsibility for their health.

In eHealth Insider’s annual look at the year ahead in January, he urged GPs to go beyond the government’s commitments and set up sophisticated, practice-based websites that can be accessed through newer mobile technologies and linked to social media platforms.

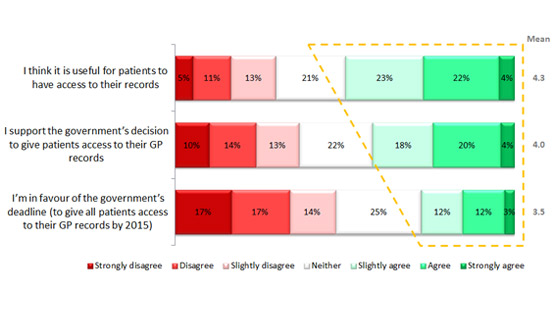

The EHI / doctors.net.uk survey suggests that GPs have accepted these arguments, at least as far as records access goes. Certainly, the survey found relatively little resistance to the idea that patient records access might be useful.

When asked whether they thought it will be useful for patients to have access to their records, half of respondents (49%) agreed that it would to some extent, with a quarter (21%) undecided, and a third (29%) disagreeing to some extent.

However, the survey suggests that GPs are not enamoured of the government’s attempts to push the issue. When asked if they were in favour of the 2015 deadline, support dropped to a third (27%), while the number of respondents undecided rose to a quarter (25%) and disagreement rose to nearly half (48%).

GPs who identified themselves as being under 30 were least likely to say that patient access to records would be useful (average score of 3.7 on a seven point range from strongly agree to strongly disagree) and least likely to support the government’s deadline (3.4).

It was GPs who identified themselves as being 60 or over who were most likely to back both access (5.1) and the target date (4.5). The survey did not include space for free-text comments, but there are logical reasons why this might be the case.

Older GPs are more likely to be partners, for example, and so more likely to look for business benefits from records access. Older GPs may be more likely to care for a number of years for patients with long-term conditions, and so be more likely to see circumstances in which records access would be useful.

Or they may just see how access could benefit patients of their own generation. But the finding puts the lie to the idea that it is a younger, ‘tech savvy’ generation that will get patient-facing IT into practices.

Email consultations; not gaining traction

The survey also asked some detailed questions about another pet idea of many policy makers and government ministers – that GPs should do more business with patients electronically.

When he launched the ‘Power of Information’ strategy, then-health secretary Andrew Lansley drummed up some newspaper interest by claiming that it would also promote email consultations, ending the “8am rush” by patients for the few slots available in most practices most days.

Again, the NHS CB’s mandate backs this up, saying that in addition to access to their records by 2015, patients should be able to book appointments and order prescriptions online, and communicate electronically with their doctors.

“The option of e-consultations,” it added, should be “much more widely available.” The EHI / doctors.net.uk survey suggests that it could hardly be less available at the moment.

Some eight out of ten respondents said they had “never” held an email consultation with a patient, while a further 4% of the total sample said they’d tried it and “no longer do this.”

Of the remaining one in five GPs who do hold email consultations, 14% said they did this only once a week, and only 3% said they did this more than twice a week.

.gif)

The British Medical Association is not keen on email consultations. In response to the ‘Power of Information’, it warned that practices could be “deluged” with extra work through this route, and urged extensive piloting of the idea.

Yet other doctors’ organisations have been marginally more enthusiastic. Back in 2009, the Medical Protection Society concluded that “email consultations can provide patients with a useful means of accessing their GP.”

However, it advised GPs to make sure that patients were happy to communicate this way, to save email consultations in patient notes, and to see patients if their problems were “complicated or difficult.”

Despite this, the survey suggests that many GPs are yet to be convinced that email consultations can be useful, safe or reliable.

GPs who said they had never tried email consultations were most likely to say they were not appropriate (average score 2.9 on a seven point scale running from strongly agree to strongly disagree), safe (2.7) or reliable (2.8).

And it was GPs who said they use email consultations relatively frequently who were most likely to say that they were all three (5.3 for appropriate, 4.6 for safe and 4.8 for reliable).

Again, this conclusion may not seem surprising. But it does suggest that GPs who have taken the plunge, and started to use a form of communication that is near-ubiquitous in other walks of life, have found few problems with it.

Indeed, the survey also found that it was those GPs who used email consultations most frequently who were most in favour of opening up records access to patients. Once doctors start using one new technology, it seems, they are keener to start using others.