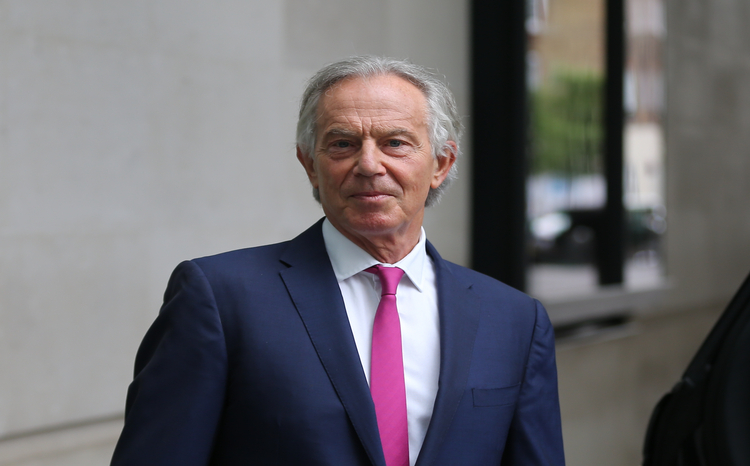

Blair Institute calls for crash programme of digital health records

- 20 August 2024

- A report from the Tony Blair Institute for Global Change calls for the creation of digital health records for all UK citizens within five years

- It argues that person-centred health records would help ensure that the NHS is ready for the "artificial-intelligence era”

- The report calls for new legislation to change data ownership rules and mandate interoperability on suppliers.

The Tony Blair Institute for Global Change has proposed a crash programme to create digital health records (DHRs) for all UK citizens within five years.

In the report, ‘Preparing the NHS for the AI era, a digital health record for every citizen‘, published on 19 August 2024, the institute argues that person-centred health records would drive improvements to health and care and shift health services from treatment to prevention and help ensure that the NHS is “ready for the artificial-intelligence era”

The institute calls on the government to commit to a DHR for every citizen within one term of parliament, developed as a “non-proprietary resource”, building on existing initiatives rather than starting from scratch.

It also calls for new legislation to change data ownership rules and mandate interoperability on suppliers.

The proposed DHRs would focus on safely collecting and storing the personal health data of every citizen, with citizens able to share that data with chosen third parties.

The report describes the proposed longitudinal records as a “single source of truth” for individual’s health and care data, with data being separated from applications.

It notes that individual’s health data currently sit in silos across hospitals, GP practices, pharmacies and phones and argues the proposed citizen health record would provide a fundamental building block for modernising the health system.

“The DHR will have most impact in primary care,” states the report. “It is out of hospital where the impact of an integrated, digital, longitudinal health record will be felt”.

The report cites examples of a range of DHR and personal health record (PHR) type initiatives in Estonia, India, the US, Israel and Spain, as examples.

Examining the UK landscape of DHRs, PHRs and shared health and care records, it says that efforts to create integrated care records around the patient have been “fraught with difficulty”, subject to cancellations and delays often due to failing to address privacy concerns.

The summary care record, which dates back to the NHS National Programme for IT (NPfIT), which launched in 2002, is described as “very narrow”.

The flagship NHS App is, meanwhile, described as “a narrow but nationally available solution”, that “can display basic information from the GP record and pathology results” with information from secondary providers to be added soon, but the report notes data “is only available for patients to view” and it offers limited functionality.

The report says use remains limited because many GPs, as sole data controllers of their patients’ health information under GDPR legislation, “are understandably reticent to share it for fear of data breach and litigation”.

The report further states that a key problem with data integration in the UK is that while open APIs and interoperability standards are almost universally stipulated as part of NHS supplier contracts, “they are rarely enforced because the UK lacks the legislative framework to compel vendors to comply”.

Other personal health record initiatives name-checked are PHRs tied to big hospital EPR programmes, such as that in Manchester.

Another variant cited is combined intelligence in population health action (CIPHA) programme, delivered by Graphnet, linking together population health data and records across 11 integrated care systems.

Patients Know Best personal health records; and Apple initiatives with Milton Keynes and Oxford University Hospitals, to enable patients to access record on their phones are also mentioned.

One notable omission is any detailed mention of regional shared health and care records that have successfully evolved over the past decade or more.

Also mentioned are the federated data platform (FDP) and secure data environment (SDE), neither of which offer patients any direct control of their data or insights. The report notes that progress on FDP has been slow.

Appearing to take its cue from heroic timescales of early NPfIT under New Labour the report states: “We propose that the government establish a dedicated unit within the DHSC to deliver this new resource.

“This department should report to the health secretary and aim to have a working minimum viable product for the DHR within two years, and a comprehensive record within five years”.

It recommends that the government legislate to make the health secretary a joint data controller with GPs, and that the government should legislate for interoperability.

The report says that as previous attempts to enforce interoperability through contracts with providers have failed, the government should pass legislation similar to the 21st Century Cures Act, the US federal legislation that mandates the use of interoperability standards.

Speaking at the Tony Blair Institute for Global Change’s ‘Future of Britain’ conference, in July 2024, health secretary Wes Streeting pledged that the new government will make Britain “a powerhouse for the life sciences and medical technology”.

In January 2024, the institute published a report calling on the NHS to establish a new public-private NHS data trust to commercialise and sell access to anonymised NHS medical records to help develop the biotech and AI sectors and new treatments for patients.

2 Comments

This display of arrogance and lack of self-awareness is astonishing.

Lest we forget – NPfIT was Tony Blair’s brain child following a cosy meeting with Bill Gates – let’s learn from Microsoft.

Choose and Book was Tony Blair’s brain child following a cosy meeting with Stelios Haji-Ioannou – let’s learn from EasyJet.

NPfIT was dogged by political interference from its inception.

The programme team was indirectly pressured to align key project delivery milestones to the General Election cycle. Already tight deadlines (a multi-billion pound procurement in under 12 months from OBS drafting to contract signing) were made even more challenging. Examples include introducing choice into what was originally a simple electronic booking system project in mid-flight, removing social care systems and interfaces from the scope and adding GP systems to the scope without consultation with established suppliers. All this combined with a naïve belief that, if you throw a few billions of pounds at a problem, multi-national suppliers will find a solution.

This was compounded by the incredible decision to disband the Modernisation Agency – which was supposed to deliver the business transformation the NPfIT solutions were designed to enable.

What we were left with were very complicated contracts for what was essentially a mixture of vapourware and “interim” antiquated PAS and diagnostic systems with precious little money left over for change management and training.

What Lessons Learned from NPfIT does the Tony Blair Institute suggest we apply here?

Joe’s right – the people who know where the NPfIT bodies are buried are almost all retired or dead now.

The NHS seems ripe for politicians with simplistic dreams to come in with a technological panacea. Instead, most people would rather they address the root causes which are poor public health, a complete lack of health education, decades long under-investment, a fragmented health service and an almost non-existent care service both with utterly worn out workforces.

The report is an interesting read and there is much in it which you can’t argue against, patient centric, interoperable, single source of truth, research powerhouse etc. All good. What is missing a lessons learned section and an understanding of how to get from our expensively acquired broken jigsaw of an installed base to the desired future. As always the anthropological and sociological issues which make this stuff difficult are not considered. The soft stuff is the hard stuff and no matter how big your parliamentary majority you can’t simply legislate away peoples right to confidential medical records. I fear that as my generation retires the organisational memory of NPfIT will be deleted and we will do another lap of the oversimplification of NHS IT.

Comments are closed.