The ‘Personalised Health and Care 2020’ framework, issued in November 2014, was the National information Board’s bid to revolutionise the use of digital technology in the NHS.

One aspect of the framework that attracted relatively little notice – despite its real impact on many clinicians – was confirmation that by 2020 the NHS will adopt a universal system for clinical terminology in the form of Systematised Nomenclature of Medicine Clinical Terms, or SNOMED CT.

This means that Read Codes, another popular but older system for clinical terminology, will be phased out.

The writing has been on the wall for Read Codes for some time. Back in 2011, the Information Standards Board for Health and Social Care officially approved SNOMED CT as a ‘fundamental standard’.

But it’s only recently that the Health and Social Care Information Centre has clarified the timelines for the switchover: all primary care systems need to adopt SNOMED CT by the end of December 2016 and the rest of the healthcare service most follow suit by April 2020 when all versions of Read Codes will be withdrawn.

The long Read

The history of the NHS using coded terminology to identify clinical concepts, such as diseases, symptoms and treatments, really begins in the 1980s at the birth of computing systems for GPs.

Tim Benson, author of ‘Principles of Health Interoperability HL7 and SNOMED’, gave the inaugural James Read Memorial Lecture in 2011.

In this, he explained that at the time he was trying to make an impact with Abies Informatics, the company he founded at the beginning of the decade as the first commercial GP computer supplier in the country.

Dr James Read, a GP, was closely involved with Abies and helped to set up the Abies User Group – an organisation he chaired for several years.

When Abies decided to create its own clinical coding system, after obtaining a grant from the government and dismissing earlier attempts that were on the market, it was Read who undertook the monumental challenge of editing thousands of codes for the different diseases, medications, symptoms, procedures and other clinical terms that doctors need to record.

It was a task that took thousands of hours and the final Read Codes (as the Abies Medical Dictionary came to be known) were delivered in the middle of 1986, two years later than expected.

It wasn’t an entirely technical task though. In his lecture, Benson explained that Read used to write all the codes on a sheet of paper using a fountain pen – before posting them to the company’s secretary. “I do not remember James ever using a computer himself, for this or any other task,” he says.

In 1988, a joint working party of the Royal College of General Practitioners and the British Medical Association recommended that the codes be adopted nationally. The codes were then bought by the Department of Health in 1990, in a move that secured their widespread use in the NHS.

What is a Read Code?

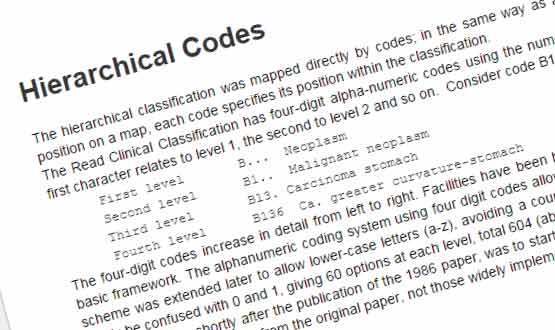

As for what Read created, the premise of Read Codes is based on a hierarchical classification, where each clinical concept has a parent code representing a disease, procedure, occupation, history, examination, prevention or administration.

Each code has up to a maximum of four other characters to further define the concept. All these characters are either a numeral 0–9 or a letter A–Z, while later updates have allowed for lower case letters to identify more concepts.

For example, G is the parent term for disease of the circulatory system. By adding up to a maximum of four extra letters or numbers, a code can more closely define the type of disease (G7 is cerebrovascular disease, G71 is a cerebral haemorrhage etc).

It’s a system that is relatively simple and usable for GPs but has proved to be restrictive and is now out of date. For instance, Read Codes struggles to cope with the multidimensionality of medicine – a broken leg can be identified as a fracture but it can also be a condition relating to the leg.

The inability to update the codes mean there are some glaring anachronisms: sexual orientation remains categorised as a mental disorder, while several terms are no longer current, incorrect or misspelt.

And Benson is particularly critical of their use in hospital setting. “Read Codes have failed time after time in secondary care,” he told the audience of last month’s meeting of the National User Group for Emis Health, one of the country’s largest suppliers for GP systems.

For many, the younger, more flexible SNOMED is the answer to these problems.

A chance of SNOMED

SNOMED CT has roots that stretch back to 1965 when the Systematised Nomenclature of Pathology was published by the College of American Pathologists. Ten years later, the CAP expanded SNAP to create the first instance of SNOMED, with updated versions released over the next decades.

It was around the end of the 20th century that Read Codes and SNOMED came together following a project to merge CTV3, the most recent version of Read Codes, and SNOMED RT, a version of SNOMED developed by CAP and Kaiser Permanente.

The result – SNOMED CT – was released in January 2002 as an international code that could work with systems across the world.

Now owned and managed by International Health Terminology Standards Development Organisation and SNOMED CT is available in more than 50 countries.

It gives unique ‘concept ID’ to every clinical term, which does not contain any implicit meaning, giving it an advantage over Read Codes as it doesn’t limit the number that can be created and what part of the hierarchy it needs to be in.

A HSCIC spokesperson told Digital Health News: “SNOMED CT has been structured in a way that allows it to evolve more flexibly than older coding technology, so that it can be more easily adapted as healthcare needs and practice develops and so technology across the system can be connected more easily.”

SNOMED has its own issues, however. Users need a specialist browser to actually use the system, while there is also a need for reference sets to handle the more complicated hierarchies of clinical concepts.

The big switch

Although many systems from US suppliers, such as CSC’s Lorenzo, Cerner’s Millennium, and Allscripts’ Sunrise use SNOMED CT, the home grown systems from the likes of GP suppliers Emis Health and TPP still use Read Codes.

The clock is now ticking on these UK suppliers to make the switch, while ensuring all records remain intact and clinicians are comfortable with the new way of working.

At the recent Emis NUG meeting, the group’s chair Dr Geoff Schrecker, a GP in Sheffield, said the move will have a significant impact on GPs who use the Emis Web system.

“I think from our end there are going to be big issues over the user interface. As a NUG, we would like our user base to be involved sooner rather than later in the user interface end of SNOMED development,” said Schrecker.

Responding to Schrecker’s comments, Chris Shepherd, head of product management at EMIS Health, said the company was “fully committed” to implementing SNOMED.

“The read codes are already mapped to SMOMED in Emis Web. Our health informatics team is currently engaged with the HSCIC and a number of other bodies to make sure we implement this in a seamless way so that users are not impaired by it.”

Responding to a question from Digital Health News on whether any record will be corrupted in the switch, Dr Shaun O’Hanlon, chief medical officer at Emis, said that the company has been collaborating with the HSCIC and other providers to ensure “secure and efficient migration”.

“Our SNOMED CT program will seamlessly migrate users from READ v2 to SNOMED-CT, including both the clinical records and all of the templates, protocols, documents and other resources. We will work through issues to ensure that there is no corruption or loss of data.”

A spokesperson from TPP said the company is also working with the HSCIC to make sure its SystmOne addresses both the “technical and practical challenges associated with the introduction of SNOMED CT across primary care.”

Getting ready

As the deadline for primary care switchover gets closers for suppliers, so it does for GPs. “The issue fundamentally around all of this is to know exactly what you are doing and why,” said Benson. “The solution is education.”

The HSCIC has several resources on its website, including a series of live and recorded webinars and the opportunity to organise formal workshops.

A spokesperson added that HSCIC is “establishing a dedicated team to help care providers, system suppliers, clinicians and other stakeholders”.

IHTSDO also provides some resources, including a 57-page SNOMED CT starter guide and both foundation and implementation e-learning courses.

Despite this, when Benson asked delegates at the Emis NUG if they felt competent using SNOMED, he got an almost complete absence of hands for ‘yes’. This shows the amount of work that remains to be done in a relatively short space of time.