I remember the quiet thump of NICE guidance arriving at the practice from the days when I was a GP.

The day the latest NICE missive on treating depression in primary care arrived we happened to publish this story on Patient Opinion:

“Since 2000, I have suffered three episodes of psychotic depression. On each occasion I danced myself back to health. My mother also suffered from depression and in the end committed suicide.

“The care I received has been good, but it is the dancing that has both lifted me and grounded me. I believe I became ill because I did not listen to my feelings enough and lived a life that was not true to myself. Art is an important part of self-discovery.”

Needless to say dancing did not figure in the NICE guidance.

So what should we make of this? You might think it is simple – my job as a GP should be to make sure that the patient gets the evidence and nothing but the evidence.

But I have now asked audiences at many conferences – well over a thousand NHS staff – what they, personally, would want if they or their daughter was depressed.

Would they want their daughter’s GP to spend her ten minute consultation implementing NICE guidance? Or would they like the GP to explore how their daughter could “live a life more true to themselves?” Less than scientific, I grant, but audiences vote overwhelmingly for exploration not evidence.

This tensions between the evidence and what patients – and perhaps the majority of NHS staff – want are deepening because the web is changing the nature of knowledge itself.

In the old days (that’s the 20th century to you and me), when evidence-based medicine was still in nappies, experts used to filter out anything that wasn’t deemed essential. This gave them a lot of power.

Now the web (aka Google) just filters the important stuff forward, leaving everything else, both sense and nonsense, just a click away. Each article, each reference, each ‘fact’ links out to an infinity of interpretations.

Evidence no longer seems so simple when everyone can see all the gory details under the bonnet – all the biases and conflicts of interests laid bare and all the counter arguments snaking away into the distance. (This shift from ‘filter out’ to ‘filter forward’ is brilliantly explored in David Weinberger’s book ‘Too Big to Know’).

We live in a world drenched in information; a world where it is becoming harder and harder to say why my view is better than yours.

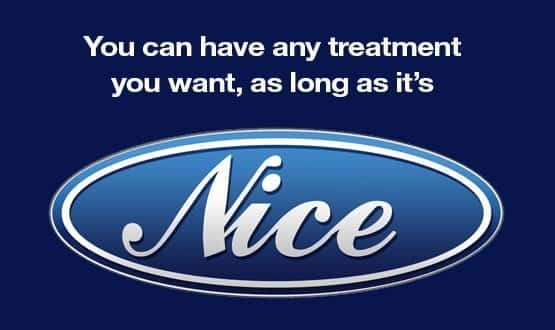

Meanwhile, the NHS has morphed Henry Ford’s adage “you can have any colour you like as long as it’s black” into “you can have any treatment you like as long as it’s NICE”.

In this centralised, evidence-dominated world deviating from the straight and narrow path(way) is a Bad Thing and the state has erected a regime of discipline (aka NICE, QoF, many other acronyms) to make sure that frontline staff do what is “best for patients” (though not necessarily best for “this” patient).

The question is not whether this is wrong (lots of diabetics and heart patients and asthmatics are getting more consistent care as a result) but whether it is sustainable in the age of the web.

It’s not just that the web delivers a torrent of conflicting “facts” to everyone connected to a smart phone, it also gives everyone a voice to comment, discuss and dissent.

Indeed, it sometimes seems that Mystic Meg’s thoughts on homeopathy carry as much weight with the public and more weight with the Daily Mail than all our finely polished pearls of wisdom.

So what’s to learn from all this? Firstly, that people are increasingly using their public voice to articulate what they want. Secondly, that these wants may not correlate with the evidence.

Finally, that these public voices and the increasingly conditional nature of “facts” is likely to lead to a crisis of authority within the current NHS mindset.

NICE has been a handy way to hold the line against demand, but it rests on the assumption that evidence and the public interest can be forged into workable political compromises that make health care affordable. As the idea of authority based on knowledge becomes contested, this is a line that may not hold.

Knowledge is no longer a thing, a summation, a life time spent studying the stars. Both knowledge and authority are becoming properties of the network itself.

Our world is already full of informational fabrics. Google was our swaddling clothes, wrapping us in any information we desire.

GPS was our baby bouncer, guiding us through an always-mapped universe. Mobile phones have killed solitude and Facebook makes a billion social networks visible.

Information fabrics are created by layering a sophisticated technology over a humming human network. Imagine the NHS clocking its one million consultations a day through an electronic record that correlates symptom inputs with therapeutic outcomes and you begin to see, however dimly, the future of medicine.

That future is a socio-technical dance of millions of interactions, each mediated at human scale, but guided by the collective, ever-increasing knowledge inherent in the network itself.

Paul Hodgkin

Paul Hodgkin is chief executive of Patient Opinion, a website on which patients, service users, carers and staff can share their stories of care across the UK. Patient Opinion is a not-for-profit social enterprise based in Sheffield.

Until 2011 Paul also worked as a GP and has published widely including in the BMJ, British Journal of General Practice and the Guardian and the Independent. Follow him on Twitter @paulhodgkin.