Partnership Working – Advisory Series, April 2018

By Maja Dragovic – Digital Health

Digital’s ability to support greater partnership working in healthcare has been frequently touted. But, as Maja Dragovic reports, it’s also increasingly proving the means or motivator for initiatives which extend partnerships beyond health and into broader care.

As regions across the country bid for national investment in shared health and care records, the potential for digital to help forge collaborations within and beyond the NHS has once again been highlighted. Local Health and Care Record Exemplars (LHCREs) will initially be focused on developing shared care records, but the intention is that – in the longer term – they will open up possibilities for greater collaboration and integration across a local care landscape.

But LHCREs aren’t the only national initiative with digitally-supported partnership working as a stated aim. Venture into the local government sector, and you’ll uncover the Social Care Digital Innovation Programme. Developed in collaboration with NHS Digital, the programme sees the Local Government Association (LGA) award funds to councils developing digital technology projects to improve social care.

Councillor Izzi Seccombe, the chair of the LGA’s Community Wellbeing Board, reports that “many” councils are “already harnessing the powers of digital technology to transform social care services and support integration with health partners”.

Large partnership

Take Sunderland, for example. According to Paul Gibson, the clinical commissioning group (CCG) and council have long been collaborating on integration of services – such that they were awarded NHS England vanguard status in 2015 for a model designed to offer a recovery at home service.

“A lot of the focus was on patients that go into hospital a lot; it was all about supporting those patients more in the community so they are not being pushed into hospital,” explains Gibson, head of informatics at Sunderland CCG.

The setup brings together organisations from primary care, community services, acute trust, urgent care services as well as the city council, social care services and mental health. Services are concentrated in a hub “that has a lot of social care and city wide services from healthcare perspective all working together”.

But using digital to harness such a collaboration proved technically tricky. Among the issues: differences in clinical coding between GP practices and social care. Never mind the challenge that Sunderland Care and Support, via which the services are delivered, “were largely still reliant on things like spreadsheets and paper processes”.

There was also the problem of gaining trust between all relevant parties. “GP practices have lots of ownership over their patient records that they’re responsible for,” comments Gibson. “It took a long time to get them to open up and be comfortable with the whole sharing approach.”

A governance group was therefore set up that included included clinicians, GPs, social care staff, practice managers, and others involved in the sharing of data. “That’s where we had the discussion about who should have access to what and at what level. We see that sharing group infrastructure and the governance is actually key to moving forward.”

Including the third sector

In the longer run, Gibson believes it will also be possible to use digital to increase third sector involvement in health and social care, and drive stronger partnerships. But he believes here too interoperability might be a stumbling block.

“The challenge that we’re always going to have with the third sector is: a) do they actually have any underlying infrastructure ie. NHS network connectivity which is a must and b) do they have information systems that are able to hold the right data – so that comes back to coding.”

For John Loder, head of strategy at innovation charity Nesta, information governance is also an issue. “Our experience is that people are generally reluctant to share data outside the NHS circle without the explicit consent from the individuals, which makes it very cumbersome to gather.”

Loder believes, however, that patient-focused charities can play a larger role when it comes to data collecting. “Patient-orientated charities are in a great situation to get their their own data from individuals. In doing so, they can start from a different point.”

“There is high quality information on advice and support, building online peer-to-peer networks, there’s leveraging their brand to gather high quality research data. They are going to play an increasing role in the healthcare environment.”

And while information governance might sometimes limit the scope of collaboration, Loder reports the NHS is funding projects with the third sector. “We’ve got some funding from the NHS for our Dementia Citizens initiative,” he reports, “and they sat on our steering group and they are very interested in it”.

The project developed two apps that people affected by dementia could use to enjoy activities – such as listening to music or creating a digital life story book – and which can also be employed to complete wellbeing surveys.

Connecting with teenagers

Handheld devices have also proved a means of increasing partnership working in other areas of the country. In the Midlands, for example, a service developed by staff at Leicestershire Partnership NHS Trust but commissioned by the local councils is providing teenagers with confidential help and advice via text messaging.

ChatHealth is a service for 11-19 year olds, and according to clinical lead Caroline Palmer, its development involved close collaboration with the Royal College of Nurses, the police, the NSPCC, school nurses and practitioners who work with young people.

She says its big draw for young people is that it allows them to remain anonymous. “They can ask those embarrassing questions that they’ve been worrying about that there’s no-one to ask or talk to about. They can be anonymous. But then we need to be assured that we’ll be able to follow the process to support that young person’s wishes to remain anonymous.”

Challenges ahead

It’s an issue which touches in part on what some see as another obstacle in the move to digital supporting more partnership working between health organisations, into social care, and through to the third sector. For John Loder, four letters are looming large in his mind: G, D, P and R, and the rights this new European Union data protection regulation gives to people.

“One of the big issues [of the general data protection regulation] is to have the right to have your data removed from a dataset,” says Loder. “This means that if you are a person that is responsible for that data, you can’t really let it out of your control, otherwise you can’t be certain that you have eliminated it on request.”

And from an interoperability aspect, healthcare still seems to be lagging behind industries such as banking and finance, says Gibson.

“I think there is a big challenge in terms of what people’s expectations are but when it comes to working with multiple organisations. They are all in different places in terms of levels of maturity and that has to be recognised,” adds Gibson.

One of the major challenges to collaboration that involves multiple organisations across a large area is who owns the data and who pays for it, Gibson points out.

“We need to get our heads around what is that model. What is the vehicle for taking these things forward especially when you work in NHS whose infrastructure changes continuously?”

Integration for millions of patients: working together for NHS whole-system interoperability

By InterSystems

Big changes are happening as the NHS strives to be more efficient and save billions of pounds. Interoperability is a well-used term in Healthcare IT, but is something that all clinical leaders and managers need to have an understanding of. At its simplest, interoperability is “the ability for IT systems to exchange information and for the systems to be able to reason on the data that is exchanged”.

Therefore, when information from one system is interfaced into another, it is as if the data coming into the receiving system has been entered through the applications own user interface. Whole-system interoperability is connecting different care settings and across social care, the third sector, education, etc. knitting together currently disparate systems and organisations.

Integration and interoperability are long sought-after goals. Technologies like portals have played an important role in connecting information for now, but rising digital maturity and the increasing prevalence of electronic patient records (EPRs) beyond just primary care, Electronic Palliative Care Co-ordination Systems – EPACCS, Social Care Case Management Systems are creating the demand for more sophisticated interoperability, where health and care professionals really can see absolutely everything about a person from every care setting through their own primary system. The NHS will achieve whole-system interoperability to meet frontline demands.

Rising digital maturity means new demands from clinicians

Interoperability projects of the past have failed to reach out to all care settings. New models of care, and the reconfiguration of health and social care, require that systems, organisations and care workflow be truly person-centric and not organisation or service-line centric.

With rising levels of digital maturity, the NHS will soon have much of the technology it needs to match personalised care ambitions and to realise new interconnected models of care. Many parts of the NHS, including a growing number of acute trusts, already do.

The key challenge is joining up these technologies and this must happen quickly.

As digital maturity advances, people at the frontline of delivery need access to information in one place. That does not mean logging into separate systems to access information, however available those logins may be.

Once familiar with their EPRs, clinicians want to access information in that one system, even if that information is held outside the organisation. In a world where clinicians are accustomed to incomplete information, they will not spend their time searching for it in multiple systems.

Clinicians are now demanding a comprehensive approach to interoperability from within the NHS, so they can make full use of EPRs, systems which have required major investment and which, from the user point of view, need to be able to talk to their counterparts across the entire care spectrum.

Responding to new demands – the completeness of standards is finally materialising

Interoperability must be achieved in the truest sense of the word to respond to this clinical demand, based on expectations. Information can no longer only be interfaced, but the receiving system must be able to process and understand that information.

Ultimately the NHS is moving to more digitally mature systems – where acute providers need to connect their EPRs with community, primary care, social care and others across a whole system.

One of the reasons why interoperability in healthcare has been so difficult is that healthcare standards have been insufficient. Comprehensive, flexible and internationally agreed-upon standards are needed to enable a new way of working focused on structured data. Healthcare standards must mature and are showing signs of doing so. The completeness of the standards is finally, at last, materialising.

Extending capabilities without building something new

Mature interoperability also means that existing capabilities can be extended and adapted to meet new requirements without having to build something new. It became clear to CMC that End of Life systems (Electronic Palliative Care Co-ordination Systems – EPaCCS) can provide valuable communication and coordination for wider cohorts of patients, i.e. other than those in the last year of their lives.

This includes adults and children who are vulnerable in other ways, as a result of long term conditions, physical frailty, homelessness and cognitive impairment. In other words, anyone who might benefit from a crisis care plan. Having an interoperable solution means that what you have can be extended and re-used, for example to deal with the concept of urgent care planning for those who need care at 3am, regardless of their prognosis.

We need a set of tools in the box, not immediate perfection

Work in England is under way to make interoperability clinically driven. The Professional Records Standards Body has been central to the definition of the urgent care plan in London.

Despite recent steps, there will still be many systems out there that will not talk HL7 FHIR or CDA. There must therefore still be a capability to allow these systems to interoperate with those that do. Some problems are better solved by HL7 FHIR, others by CDA and perhaps other problems using other standards.

The NHS must not try and leap to perfection in a single attempt. It will need a set of tools in the toolbox to allow all systems to participate and exchange structured and coded data, even if they don’t conform to these latest standards.

By focusing on the most urgent clinical integration priorities first, the NHS can show others what “good” looks like.

| |

| Contact number: 017 5382 9647 Email: Erica.Bennett@InterSystems.com Our website: www.intersystems.com/uk/industries/health-and-care/nhs/ Twitter: @InterSystemsUK LinkedIn: www.linkedin.com/company/intersystems-uk/ Facebook: www.facebook.com/InterSystems/ Further reading: Enabling efficient care in turbulent times Joined-Up Health & Care 2018 | |

Integrated care relies on system-wide partnerships

By Cerner

On the voyage to integrated care, there is, unfortunately, no quick fix. In a sea of information, transient populations, multiple co-morbidities and complex health and care system challenges, technology can provide a boat for your journey, but everyone needs to grab an oar and row together. Often it will take a determined captain to get everyone on board, help steer and keep the crew pulling in the same direction.

Analogies aside, the need for strong and effective partnership has never been greater. If one thing is certain, it’s that integrated care is wholly dependent upon strong partnership between all parties – including commissioners, primary care, acute care, community, mental health, third sector, social care, suppliers – and your citizens.

Integrated care faces challenges of connecting siloed information, changing models of care, and building the business case for wider system change. By sharing your vision through networking and collaboration, you will be saved from having to reinvent the wheel, learn from others’ experience – both positives and perhaps not-so-positive – and receive increased support. System-wide intelligence and technology can certainly help, but not in isolation – while they can act as enablers, it is partnerships are the key to unlocking your organisation’s potential.

However the partnership charts its course, the route and destination must be shared by all parties and it must be based on delivering value – for the health and care system, the public purse, the clinician, and ultimately for the citizen and their community.

At Cerner, we are focused on developing strategic relationships and collaboration that creates value across the health and care continuum. We’re proud to call our clients partners, and alongside many of our fellow suppliers, we are building relationships that nurture innovation and enable smarter care, better outcomes and healthier communities.

So, pack your bags and hop aboard. The waters may get choppy, but the destination will be worth it.

The value of engagement – a practical case study:

![]()

Wirral Partners – a group of three NHS Trusts, the local authority, CCG and professional committees (medical, optometry, pharmacy, dentistry) – are on their journey to integrated care and population health management.

They’ve found engagement and transparency with the system partners to be an essential component in their ongoing business development and planning that aims to change the way care is delivered for 320,000+ citizens – ultimately keeping them healthy and out of hospital.

A unified approach

The premise of their Healthy Wirral programme is to shift the focus from ‘what’s wrong with me’ to ‘what’s important to me’. To make this a reality, it was essential that local health executives buy in to the idea to support the business case and opportunity for real change. In order to encourage this, Cerner worked alongside Wirral Partners on their system-wide programme of transformation, to help develop new models of care and proposed service improvements across the health and care system.

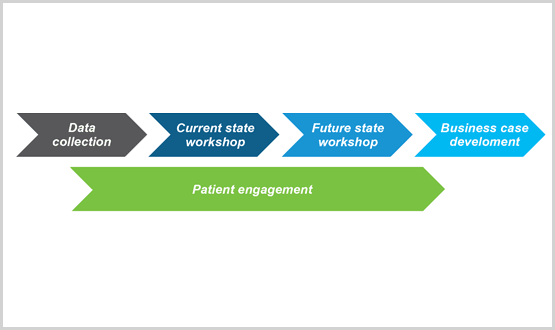

The approach taken was focused on the end-to-end patient pathways, engaging the health and care providers involved in the pathway redesign across the system, with diabetes, asthma and COPD (respiratory) prioritised for the first phase of work. This summary shows the practical process Wirral Partners undertook to get engagement that underpins success.

Stage one: Data collection

A great deal of data was collected from partners, clinicians, patients and citizens to help inform how patient pathways currently operate. Process observations and interviews were held at a number of health and care providers involved in the end-to-end patient journey to identify existing challenges. Financial data was also gathered to provide a cost analysis of the patient pathways.

‘Improve early support post diagnosis’ for diabetes and ‘more patient education needed’ for respiratory conditions were highlighted as key objectives.

Stage two: Current state workshops

Cerner supported Wirral Partners in taking a value stream analysis approach and walking through the pathways in detail to identify process steps that add value and those that do not or cause unnecessary delays. The data gathered prior to the events was displayed to provide a view of care at a population level.

Workshops led by a senior public health member of the CCG, with active involvement from project sponsors, reviewed and assessed pathways, and identified and prioritised opportunities for improvement, with the group considering the biggest impacts on patients.

Stage three: Future state workshops

The next stage focused on exploring the ‘art of the possible’, developing persona-based scenarios to consider care from the patients’ perspectives, and mapping out the future state model and pathways. The workshop was attended by professionals from multiple providers, partners from national patient groups (i.e. Diabetes UK and British Lung Foundation) to advise on best practice, alongside professionals not currently involved in the pathways, e.g. psychotherapists.

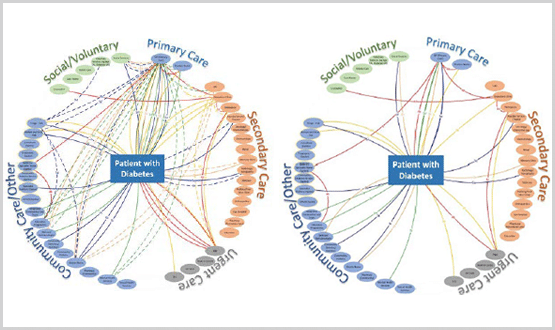

Visuals were produced to depict the different touchpoints that patients could make on example diabetes and respiratory patient pathways, highlighting the need for a ‘one stop shop’ approach and remove the ‘avoidable’ waste (see below).

Current (left) and future (right) state diabetes touchpoints:

The workshops addressed the majority of challenges encountered in the current state, with those not addressed being deemed out of scope. From there, senior stakeholders took ownership of the process and agreed on the means to identify key messages. The group also jointly came up with pledges on areas they wanted to improve, which the service leads then commitment to deliver.

Stage four: Business case development

The programme produced detailed business cases for transforming both diabetes and respiratory care in the Wirral area. These included findings, the proposed way forward, and identified cost savings on some of the key benefits. As a result, the business cases were approved by the Healthy Wirral Partnership Board to be put into action.

The power of partnership

Through partnership with local system partners and Cerner, the Healthy Wirral programme has won the approval of local executives and been able to set out proposals and recommendations for future service delivery based on all information gathered throughout the process.

The proposal involves developing an integrated community service for both diabetes and respiratory care to include:

- a one stop shop approach to ensure individuals’ needs are all met quickly in one place

- a focus on educating patients about their condition and how it affects their lifestyle

- one number for patients to call for reassurance, speedily-delivered aid, and treatment in the community

Contract models are being reviewed and discussed, and the future service delivery of these new care models is underpinned by a Cerner’s comprehensive intelligence and population health solutions with integrated analytics.

These solutions will act as powerful enablers to delivering high quality care in a proactive manner, to minimise the risk of disease progression and to identify those at risk of developing long-term conditions. These individuals can be targeted with the right interventions, delivered by the right people at the right time.

| |

| Email: CernerUK@cerner.com Our website: www.cerner.co.uk Twitter: @CernerUK | |