As the second round of bidding for NHS England’s technology fund has demonstrated, open source is very much in vogue.

The prospectus for the £240m of funding that will be available for IT projects over the next two years emphasises the value of open source solutions; and a growing number of NHS trusts appear to be listening.

As trusts look for ways to lower their software licence costs, while having greater control over the software they use, open source solutions are slowly but surely gaining in popularity. However, there is still a whole host of questions to be answered in relation to the opportunities and challenges they provide.

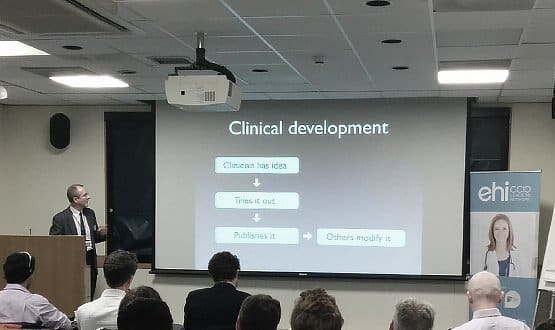

Chief clinical information officers and a range of other professionals gathered at EHI’s CCIO Open Source Conference to discuss these issues, against the fitting backdrop of a hospital leading the way in open source solutions.

Opening eyes

Moorfields Eye Hospital’s open source electronic patient record system, Open Eyes, has won praise for its ease of use and is one of eleven open source suppliers listed for trusts in the second round of the tech fund.

Attendees were taken on a tour of the hospital to see Open Eyes in action, complete with visits to the noisy data centre and the developers’ room – where the coders spent the morning frantically cleaning to make sure it was presentable.

Open Eyes director Bill Aylward said his advocacy for open source is based on its flexibility and the results that it can produce, rather than its inherent value. “I don’t want open source, I want better software, and I think open source is the way to achieve it.”

While open source solutions can mean different things to different people, Aylward says they are best defined as software where the source code is published and downloadable with no licence fee.

The benefit, he argues, is that those with enough knowledge can then share their modifications and improvements to help it work better for all users.

He also argues that a move to open source software is simply about bringing a hospital’s IT department in line with the other areas of its work. “If pharmacology was closed source, you’d be popping pills without having any idea what was in them.”

Leeds on the way

Dr Tony Shannon, CCIO at the Leeds Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust, describes the current move towards open source as a chance to move out of “the dark ages”.

Shannon, who spoke about his work on an open source clinical portal and the development of a city-wide integrated Leeds Care Record, said the flexibility and accessibility of open source is critical to meeting the constantly changing requirements of clinicians.

“If we’re going to have a 21st century healthcare system, we need to underpin it with open technology and get people to understand the processes. If you get the Lego bricks right, you can fulfil a wide variety of needs.”

Shannon described NHS England’s presence at the conference as a sign of how mainstream attitudes towards open source are changing significantly.

While Aylward and others said the body’s “cultural barrier” against open source had been an obstacle in the past, its change of heart has been welcomed by trusts buoyed by the legitimacy that the official seal of approval provides.

“I’d like to give credit to NHS England for, if you like, legitimising the push for open source: what might have seemed like a lone ranger approach now seems reasonable,” Shannon said.

Another part of open source’s legitimisation is the high level of involvement that clinicians now have in the development process, allowing them to feel engaged and connected to the finished product.

Dr Rhidian Bramley, CCIO at the Christie Foundation NHS Trust, said the needs of clinicians were at the front of his mind when developing a range of clinical web forms to capture, download and analyse data. “The key principle we stuck to was that it’s got to be really easy to use – it’s all about the clinicians.”

Money’s an issue

Despite all the optimistic talk, speakers and attendees raised several potential obstacles which must be overcome if open source is to be taken up widely in the NHS.

One issue, which Aylward and others acknowledged, is the need to strike a balance between allowing changes to a software’s code while trying to stop trusts from “forking” it into several radically different versions – lowering its clinical value and making it difficult to provide support.

Moorfields’ solution to this is the OpenEyes Foundation, a non-profit charity set up as a “custodian” of the software to ensure it is protected and developed in a way that ensures its security – an approach which others are likely to follow.

Aylward also mentioned Red Hat, an open source software company working with some trusts to provide commercial implementation services and support for open source solutions, as another way to ensure the quality of open source code is maintained.

In addition, the bottom line was never far away from people’s minds. Understandably, some trusts are reluctant to take the code for software they have painstakingly developed and to give it away without any guaranteed return; or even assurance that they’ll be able to cover any further deployment and support costs.

Some delegates to the conference argued that this problem is exacerbated by the latest round of the tech fund, which entices trusts with funding to move to open source without giving the same incentives to the trusts working on open source solutions.

As Bramley put it, “there’s no reward for people developing open source, but there is for people using open source.”

Again, though, supporters of open source argued that there is money to be made from support agreements and other new business models that will crop up as more trusts move to open source and look to capitalise on their investment.

“People say, hang on, you want to spend £3m and then give it away? But just because it’s licence-free doesn’t mean you can’t make money out of it,” Aylward said.

As he also points out, the lack of licence costs is also a potential boon for trusts with tight budgets.“There are so many examples in ophthalmic where people have contributed to the code but their trust can’t even afford to buy it – with open source, that disappears.”

Collaboration may be the goal

However, it is the clinical rather than financial potential that holds the most appeal to those working with open source.

By sharing the work they produce rather than keeping it to themselves, trusts can build up what Shannon described as an “ecosystem” for everyone to benefit from.

As Christie consultant clinical oncologist Dr Jac Livsley put it, open source offers a chance for trusts to live up to the ideals of collaboration and innovation that should be driving national healthcare efforts.

“Isn’t this the point of the NHS? I know we’re not really all in this together – we steal off each other and compete like mad – but maybe this is a way of getting back to the actual NHS, which is a national health system.”