Sweet IT, Alabama

- 11 June 2013

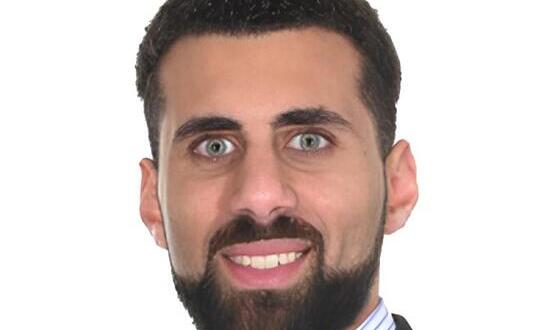

Earlier this year, Jorge Alsip stood up in a lecture theatre at the University of Alabama to begin teaching a course he’d developed on clinical informatics.

Close to 25 medical students had opted to take the module, and Dr Alsip quickly realised that they all had something in common.

“When I talk to them about the paper charts we used before computers came in, they all look at me kind of funny; as if I’ve dropped out of a time capsule,” he admits with a laugh.

“Most of our medical students today would be hard pressed to remember a time when they didn’t have a personal computer in their home – much as my generation is hard pressed to remember a time when they didn’t have a television in their home. They have grown up with computers.”

The pull of the new

In a way, though, so has Dr Alsip – when it comes to his clinical practice, at least. Thirty years ago, he was the young doctor realising that his chosen profession was not fully embracing the technology that was available.

“I was an emergency physician at a community hospital in Mobile, Alabama, and recently out of residency training,” he remembers. “At the time, half of my clinical group didn’t even own a computer, and they were scared to turn them on.

“So when we put in a voice recognition system to do our physician documentation – very early, very crude technology – I became I guess what we would call today the physician champion.”

Why him? “I don’t have any statistics to back up my impressions, but I’ve always thought of emergency physicians as a very technology-orientated group of specialists,” he reflects.

“We tend to like new gadgets, and gravitate to new things. And I was the youngest in my clinical group at the time, so that skewed it even further. This was going to be my interest.

“As I got involved in these projects, I found I really enjoyed finding ways to improve things clinically using technology. I enjoy clinical practice, but I really enjoy finding ways to leverage technology to improve things.”

Playing zone defence

As chief medical information officer at the University of Alabama at Birmingham Health System, Dr Alsip now has that opportunity each and every day of his working life. His task is not a small one. The organisation runs multiple hospitals across the state, with 1,150 beds on its core campus alone.

“When we went live with Cerner Millennium on the inpatient side, back in 2008, we were probably covering six or seven square city blocks of healthcare facilities. Just covering that many was quite a challenge,” he remembers.

The solution was to bring in fellow physicians from Cerner, and to turn to tactics more common in American football than in healthcare. “We called it zone coverage: assign one physician to every block so that we had somebody in the immediate area when a physician needed help.”

Since that initial implementation, the electronic medical record has been rolled out to more than 140 outpatient clinics. Dr Alsip calls it having “one source of truth” for critical information.

“So if a patient develops an allergy – or has an allergy documented in the clinic, or in the emergency department, or during a hospital stay here, or even while we’re getting an outpatient x-ray exam – in fact, if anyone documents an allergy at any point that information is instantly updated in every venue we have. Everyone has exactly the same information.”

He admits the change has not always been easy. “We all develop our habits, so changing anything about the way we do things on a day to day basis is tough. We’ve had some physicians who have not been real excited about change. We’ve had some who want to go even faster.

“Our job is to try to manage both. We do want to push ahead, but with appropriate caution. We want to make sure that we don’t negatively impact the way physicians are able to take care of their patients.”

Great careers ahead

Such comments explain the advice Dr Alsip would offer to anyone in the UK considering pursuing a role as a chief clinical information officer; leading on IT and information projects for a trust.

“First of all, you have to have an even disposition – you can go from being thanked and praised one minute to being cursed and attacked the next, because different people have different outlooks on what’s going on. You can’t get overly excited about the praise, and you can’t get overly defensive about the negative comments.

“You have to have good team building abilities,” he continues, “because although it’s tempting just to deal with the one person who brings up an issue, you have to make sure that what you do to fix the problem for one person doesn’t break things for another person.

“It’s compromise, and sometimes it’s getting the different players to the table to have them work out some kind of consensus. That can be a challenge.”

Despite the challenges, he sees a bright future for clinical involvement in informatics and information technology – in part because of those students who sometimes cast him confused looks at the very idea of using paper for record keeping.

“There’s a good core of young physicians in training who are interested in informatics,” he says. “And last year in the US, clinical informatics was recognised as a formal medical specialty by the American Board of Medical Specialists. So it’s now actually a formal specialty – they’re developing the initial exam, and they’ll start board certifying physicians.

“I think it’s further recognition that this is a truly a specialty that’s going to be here for the long haul, and that it is on a par with other specialties.

“We’re going to see a continuing increase [in interest]. We really saw it take off with meaningful use [the US government programme which attaches funding to the use of EHRs] and I think it’s going to keep taking off for another few years before it levels off.”