From the Heart and Chest

- 9 September 2013

Electronic patient record implementation is all about change, and at present it is “all change” at Liverpool Heart and Chest Hospital. EPR is no longer a project, but part of the ‘business as usual’ of the organisation.

We’ve said goodbye to some good friends like John Coleman, our EPR programme director; which seems odd after having him around as my close colleague (and sparring partner) for so long. But it feels good to be in BAU rather than project mode.

Not that this means the changes are over. We have well developed plans for both optimisation and future development to make us a paper free organisation.

All about change

In the UK, we are not very good at healthcare IT change; or at least we haven’t delivered it very effectively to date.

There are 119 US hospitals at HIMSS level 7, and at a recent presentation a guy from HIMSS was talking about plans for measuring higher levels of EPR development, because it now needs to be able to differentiate them.

A bit like the introduction of the ‘A*’ grade into A levels since my days at sixth form; except that I haven’t heard any allegations that the HIMSS exams have got easier.

In Europe, there are only three level 7 hospitals, but there are 27 level 6 hospitals. And of those 30 hospitals, precisely none of them are from the UK.

There are lots of reasons why we are in this state. NPfIT was a failure, but I don’t want to rake over that well-trodden path of discussion. Instead I want to propose to you, dear reader, that it is our attitude to delivering healthcare IT change that is wrong.

No to ‘trickle down’

One legacy that we have from the Thatcher era is a belief in the ‘trickle-down effect’. In the economic context, this is the concept that if those at the economic top of society are successful, their wealth will trickle down through society to make things better for all of us.

I feel that this thought process has also, to an important degree, invaded our approach to healthcare IT. If we can create islands of improvement, preferably islands of excellence, then others will adopt and emulate this, both within organisations and across the wider healthcare community.

While not without merit, I feel this ignores the fact that delivering change is a huge challenge in itself. There are books written on delivering change and people who tour the world speaking about it.

In healthcare, our number one priority is to do no harm – “primum non nocere” is quoted as being part of the Hippocratic Oath. Turning that into more vernacular form, it may seem obvious that the best way to do no harm is to “stick with what you know.”

We know paper based processes. We know their imperfections (like lost notes) but they are comfortable and familiar. Electronic systems are fine in the home, but don’t give them to us at work!

When you combine that with the fact that clinical staff are typically very busy, and one has a hugely challenging environment to deliver change in.

Clinical leadership

Given these challenges, a strategy is needed to deliver healthcare IT change. I hope no EHI reader is surprised to hear that I feel the knight on a white charger, who will help defeat change resistance, is a member of the heraldic order of chief clinical information officers.

And I’m sure that none would dare to disagree! However, it isn’t simply a case of ticking the box of “having a CCIO”.

I have been fortunate at Liverpool Heart and Chest Hospital to be allowed to help to shape the vision and strategy for EPR. Having that influence, and not just being a clinical figure head, has been pivotal in my being able to be effective.

The title is important but is secondary – at the time of writing my title is clinical lead for IT and EPR, and Caldicott Guardian. Nice and long, but the four initials of CCIO aren’t there.

An ACE time

I have just returned from ACE13; which stands for Allscripts Client Experience. This is the company’s annual client meeting and a chance to hear about developments, network and – most importantly – learn from other system users.

One of my trust colleagues who was also there told me that she felt that our EPR is not only a baby, but a prem baby compared to what some others are doing. Interestingly, however, the Americans at the event were astounded at how much change we had delivered in one single step.

Among a lot of interesting insights, one that caught my eye was a discussion around optimising the potential of an EPR.

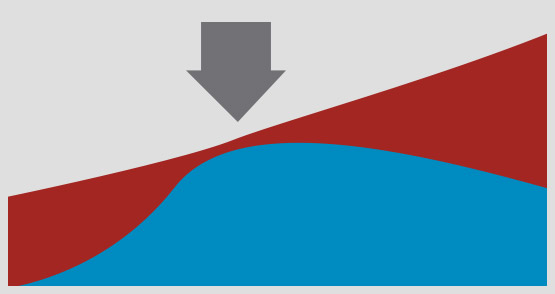

The speaker showed a slide like the one below. The red line represents the potential functionality of the EPR, which grows with time as the system develops. Organisational benefit (in blue) approaches the true potential benefit at go live (arrow) but then falls away from the red line as the new functionality isn’t adopted.

However, it actually falls in absolute terms – hence the negative slope – as aspects of EPR use that weren’t well embedded dwindle with time. Change not only needs to be delivered but also embedded if it is to succeed.

Plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose

Some things don’t change. Those of you who read my last column will be aware of my enthusiasm for Linux and free and open source software more broadly, and for my plea for its planned and tactical use on merit in the NHS.

Well, on my transatlantic flight on a major US carrier, the plane’s multimedia system was booting up as we boarded. I looked at the screen and saw the familiar Linux penguin mascot on the screen.

Clearly this hard-nosed US operator finds that Linux offers it a cost effective and high quality solution. Liverpool Heart and Chest Hospital hasn’t gone down that route, and I personally am very satisfied with the choices that we have made. But to each their own…

Dr Johan Waktare will be speaking as a ‘CCIO in the front line’ at the second CCIO Leaders Network Annual Conference that is co-located with EHI Live 2013. This year’s conference is free for all visitors to attend.