Home comforts: Surrey’s IoT trial for dementia care

Every time you switch your kettle on, a signal goes back to a centralised control room. The same thing occurs when you step out of your front door, sit down on the sofa or open the fridge.

While it may sound like an Orwellian nightmare, this is actually an NHS trial into how the Internet of Things could help dementia care.

Led by the Surrey and Borders Partnership NHS Foundation Trust, the £5 million trial was launched on 16 September and will include 1,400 participants, made up of dementia patients and their carers.

Split into two sets, 700 will be a control group and the remaining half will have unobtrusive devices installed into their homes for six months at a time.

A test bed for the IoT in health:

The Technology Integrated Health Management (TIHM) for Dementia is one of two test beds funded by the IoTUK, a three-year government programme designed to increase adoption of IoT knowledge.

Technology in healthcare is always a hot topic for NHS England chief executive, Simon Stevens, and he once again voiced his support at the Health and Social Care Expo in Manchester last month.

TIHM’s partners include the Alzheimer’s Society, University of Surrey, Royal Holloway University of London, Kent Surrey Sussex Academic Health Science Network, six Surrey and north east Hampshire NHS clinical commissioning groups and nine technology innovators.

Knowing people’s routines

The technology will allow clinicians to remotely monitor their patients, with the intention of helping them to get well sooner, and so prevent a stay in hospital.

For Helen Rostill, the senior responsible officer for this programme and director of innovation and development at Surrey and Borders, the devices that are being tested are all about finding an individual’s health signature. “We can recognise if people are deviating away from those typical patterns and then intervene.”

For people suffering from dementia – and there are more than 10,507 people over 65 with a formal diagnosis of the condition in the trust’s patch – being able to stay in a familiar environment can be critical to their wellbeing.

“We know that people with dementia do not respond well to being hospital”, said Ramin Nilforooshan, leading dementia specialist at Surrey and Borders. “Their symptoms can worsen in this environment so it is much better if we can treat them before they need to be admitted to hospital.”

Sensors, tracking devices, avatars and more

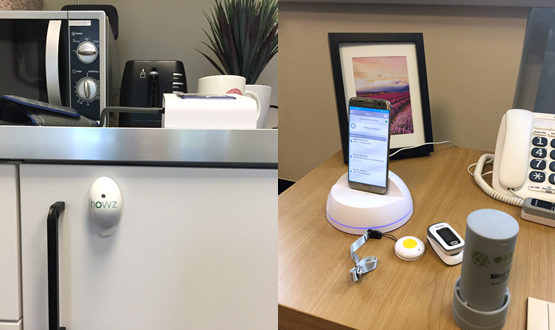

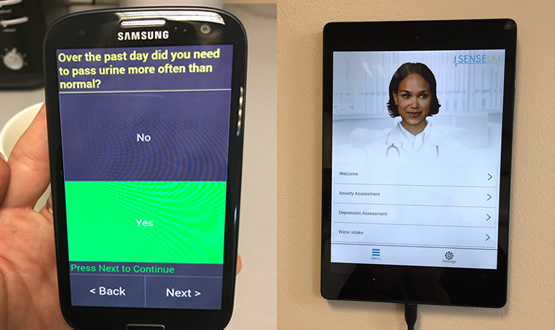

At the University of Surrey, there are two so-called “living labs” where some of the nine technology companies involved in the project recently showed off their innovative devices for remote monitoring in the mocked-up living space.

Manchester based Intelesant, has created Howz, which affixes to a door or white good to act as an electricity monitor or a door sensor. There’s also Halliday James’ St Bernard Location Service, which installs a GPS tracker into a bracelet and provides an out of home detector.

Sensely, offers virtual nurse Olivia through a tablet on the wall; the device also provides daily notifications and reminders to measure weight with the readings, which are then sent through to the central database.

The “living lab” allows for devices to be tested, and also to train carers and clinicians in how the devices work. Alongside the reconstructed home, a second living lab acts as mission control, where all the data is fed back into and alerts are noted and responded to appropriately.

A window into people’s lives

All of the information that is relayed creates what Rostill terms an “unique window into people’s lives”. However, what makes this trial more than just about data collection is how these statistics will be processed using a smart system.

As Payam Barnaghi, reader in machine intelligence at the University of Surrey, says, “just collecting data is not enough”.

With the ability to learn about each individual, personalised parameters can be produced and alerts triggered if someone misses his or her regular morning cuppa. This information is collected in a secure cloud server at the university’s central IT infrastructure.

“Part of this project is creating an ecosystem where you can integrate different pieces of information”, Barnaghi continues, “to create an intelligence operation system”.

Through combining the data that is gathered, a holistic view can be built up so help can be administered more quickly.

A common language

The technological challenge, according to Barnaghi, is interoperability. To enable the devices to communicate with each other a common language has been created using Fast Healthcare Interoperability Resources, called FHIR4HIM.

FHIR is getting a lot of attention globally and is becoming the platform of choice for the interoperable exchange of healthcare data.

FHIR4HIM is used in TIHM as a common model of exchanging data, and for the interface interoperability level hypercat is used. Hypercat is a UK-developed standard that enables free communication from any connected IoT sensor or device being used to monitor an environment.

From the hypercat the data can be pushed into the TIHM cloud. By creating the common models of specification, and using common models of gateway, Barngahi says the systems can work together.

Protection of identity

With the large volume of data being monitored at all times by the researchers, the need to protect the patient’s identity from unauthorised third parties is a critical tenet of the project.

The public’s sensitivity to data hacking was highlighted this year when Google’s artificial intelligence off shoot, DeepMind, was mauled in the press for its use of NHS patient data at the Royal Free London NHS Foundation Trust.

Stephen Wolthusen, the project leader for keeping patient data secure in TIHM from Royal Holloway University of London, said his concerns lie when the systems start merging.

“One of the things that we look after is controlling the access to the data in such a way that even if our clinicians try to make sense of some of these patterns”, Wolthusen said, “they cannot go back and identify individuals”.

The project is operating on pseudonymised data wherever possible. When it comes to the analytics side, anonymised data will be used; although this presents certain challenges, Wolthusen added.

“Trade-off”

Rostill’s sights are set far higher than just this trial: “We are aiming through this project to create a solution that is scalebale; a solution that we can deploy at pace across the healthcare sector.”

From the launch in September, the large scale trial will begin this winter and in 2017-18 conclusions and recommendations will be published. The results will not be limited to dementia however, but it is hoped that insight can be gained into other long term conditions.

Whilst to some the constant surveillance could appear as an invasion of privacy, to Rostill this is a “trade-off” that some people have to make between being monitored and avoiding a crisis that lands your loved one in hospital.

The main partners in TIHM for dementia are: The Alzheimer’s Society, University of Surrey, Royal Holloway University of London, Kent Surrey Sussex AHSN, NHS North East Hampshire and Farnham CCG, NHS North West Surrey CCG, NHS Guildford and Waverley CCG, NHS Surrey Downs CCG, NHS Surrey Heath CCG, NHS East Surrey CCG, and Public Intelligence. The nine technology innovators are: Docobo, eLucid mHealth, Halliday James, Safe Patient Systems, Arqiva, Vision360, Intelesant, Sensely and Yecco.