WannaCry one year on: a retrospective look at NHS IT’s black-letter day

- 11 May 2018

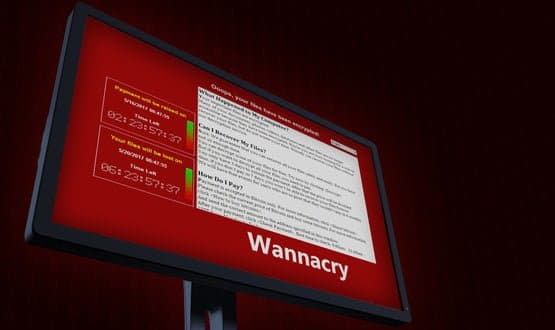

It’s peak squeaky bum for the NHS as we approach the one year anniversary of WannaCry, which devastated hospital IT systems during the ransomware outbreak on 12 May 2017.

The outbreak began on the morning of what likely seemed like any other Friday. Just after 1pm that afternoon, NHS Digital’s CareCERT unit sent an alert to the Department of Health and Social Care informing them that four NHS trusts had reported ransomware attacks affecting a number of hospitals.

By 4pm, the ransomware had spread to 16 trusts, and it was at this point NHS England publicly declared a major cyber security incident.

A “kill switch” for the ransomware was found that same evening, which prevented WannaCry from spreading further. However, it was a week before the incident was officially “stepped down” by NHS England.

By this time, the outbreak had led to disruption at least 80 out of 236 hospital trusts in England, as well as 603 primary care and affiliate NHS organisations, resulting in infected systems, thousands of cancelled appointment and the diversion of A&E patients to other hospitals.

A devastating report from the National Audit Office into the impact of WannaCry concluded that Britain’s health service was woefully unprepared for a cyber-attack of such scale, despite being warned of a threat as far back as 2014.

This included a failure to undertake basic IT security procedures, such as patching and updating computer software, and not establishing response plans for major cyber security incidents.

WannaCry, cry again?

While a repeat of last year’s outbreak is unlikely (touch wood), the suggestion of a repeat attack will be enough to have put NHS IT bods on high alert for the coming weekend.

As pointed out by Alex Manea, chief security officer at BlackBerry: “There is a need to expect the unexpected, as no one knows when the next attack will be.”

So how much more prepared is the NHS to deal with another WannaCry-style attack? Gary Colman, head of IT audit and security services at West Midlands Ambulance Service NHS Trust and a penetration tester for NHS trusts, told Digital Health News: “We’ve noted a real improvement in the security posture of some organisations, [although] that doesn’t mean we’re not still finding some real shockers out there still.”

Said shockers have come to light by no other than the NHS itself. Despite putting forth a comprehensive “lessons learnt” report from the incident, which detailed how NHS Digital aimed to prevent it falling victim to incidents of such scale in future, conflicting revelations have suggested that progress has not been as swift as it should.

In February, for example, NHS Digital deputy CEO Rob Shaw told a Public Accounts Committee (PAC) that 200 NHS trusts tested against cyber security standards since WannaCry had failed. The NHS and the Department of Health received further flak from MPs in April, who criticised a lack of progress in implementing the 22 recommendations laid out by NHS England CIO, Will Smart, aimed at improving NHS England’s cyber security agenda.

However, that’s not to say progress has been non-existent. NHS England pumped an additional £21 million into cyber security in 2017 – money that was diverted away from its paperless agenda – meanwhile a further £25 million has been earmarked for helping NHS organisations improve their defences this year.

NHS Digital is also looking to improve its security operations centre by partnering with a external firm to help deliver rapid-response capabilities.

Says Colman: “I’ve noticed a real push from IT teams re-patching and security in general. Although WannaCry was awful, it has had the benefit of pushing IT security up the agenda at many organisations.”

Recent deals penned between the NHS and Microsoft also look to shrink the bulls-eye on UK healthcare services, most notably a new licensing agreement for Windows 10, which will see NHS organisations updated to Microsoft’s latest software.

The reliance on outdated computer platforms was identified as one of the key factors that enabled the WannaCry ransomware to spread throughout trusts so quickly, so addressing this vulnerability will mean that hospitals running the software will have markedly improved first-line defences.

NHS Digital said in a statement: “Since the WannaCry incident occurred, there has been a collective focus across the NHS on strengthening resilience against cyber-attacks. We have taken the lessons learned from WannaCry and the feedback from front-line organisations to focus on improving speed of response, resilience, communication and knowledge in the event of a cyber-attack.

“Progress has been made towards many of the recommendations from the reviews into WannaCry, and we will continue to work with our partners to implement them and support health and care providers.”

Basic measures still key

Still, no organisation can ever be 100% secure against assaults from cyber-space, not least due to the rapidly-evolving nature of malware, ransomware and other cyber nasties.

Nick Bilogorskiy, cyber security strategist at Juniper Networks, said: “In the year since WannaCry, we have seen some significant changes to the threat landscape dynamic – one being that we have partially moved from ransomware to crypto-jacking.

“Ransomware attacks are only effective if the organisation has failed to back up their data, but crypto-jacking and malicious crypto mining attacks do not need prerequisites. As a result, crypto-jacking increased 8,500% in the last quarter of 2017 and made up 16% of all online attacks.

This isn’t say that criminals aren’t still using ransomware. BlackBerry’s Manea pointed out that the most basic of preparation methods can minimise or otherwise mitigate risk to data, should the worst happen.

“If you have your data backed up, there’ll be no need for you to pay up,” he said.

“WannaCry was a self-replicating virus, meaning it managed to quickly spread itself across connected computers. Storing backups in an isolated location would’ve prevented backup data from being encrypted as well.

“It’s important to have in place effective disaster recovery techniques such as keeping critical data backed up in a separate location, segregating data and the principle of least privilege.”

Needless to say, this is of utmost importance to public organisations – such as the NHS – which hold large volumes of highly personal information.

Stephanie Prior, head of medical negligence and cosmetic surgery claims at Osbornes Law, said: “The NHS holds crucial information on patients that affects care and treatment provided to that patient.

“If security in respect of this information is compromised by ineffective software systems, then already vulnerable people are at risk of further vulnerability and negligent medical care. Lack of treatment or incorrect treatment due to IT inefficiency can cause serious substandard medical care.”