Special Report: Observations and Vital Signs

Electronic observation and vital signs technology has been around for more than a decade but has it become the norm? Simon Brandon investigates.

Electronic recording of vital signs is no longer a new idea. It has now been around for more than a decade – long enough, you might think, for this technology to have proved its utility, or otherwise, to the jury.

In fact, the verdict has been in for some time, says Donald Kennedy, managing director of Patientrack.

“As far as I am aware, no one has turned off these systems after turning them on – and that’s a good benchmark,” he says. Nevertheless, the technology has not yet become standard practice.

“Based on our experience there are a growing number of hospitals that are deploying this kind of technology, but still many that are not,” he adds. “Quite a few organisations still rely on paper. We haven’t got there yet.”

In the context of the NHS, however, a decade isn’t that long, argues Paul Volkaerts, founder and chief executive of Nervecentre. He believes this technology is now prevalent, if not broadly so, in English hospitals, and that its adoption has been remarkably quick. As he points out, electronic prescribing has not been embraced as widely despite having been around for longer.

“I think the rollout has been incredibly fast,” says Volkaerts. “Much faster than almost any other technology of its kind that has been adopted by the NHS.”

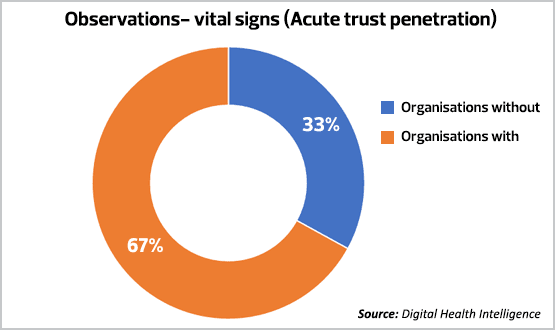

John Hopkins, chief executive of Meditrack and Civica’s partner, believes around 60% of acute hospitals now use bedside electronic observation systems of some sort. The figure is slightly higher, according to Digital Health Intelligence data, which suggests 67% of NHS acute trusts have adopted vital signs and observations technology.

“Where it has been implemented, it has been effective,” he says. “It is moving forwards. There is a lack of will and of money in some areas… but I think if you sat clinical directors or patient welfare nurses down and asked if they would have e-observations, every single one of them would say yes.”

Gathering momentum

Momentum is building; electronic observations is now mature technology with years of peer-reviewed studies detailing its benefits behind it.

“Not many digital innovations have that level of evidence yet – but this does,” says Dr Jonathan Bloor, medical director at System C.

And while he doesn’t believe there will be a specific mandate from central government around e-observations, the increasing focus on issues such as sepsis screening and NEWS2 will eventually make paper-based systems untenable.

“We will get to a position where an organisation will say, ‘We can’t keep doing this on paper’,” Bloor says.

“These things drive the need to collect data reliably… there is a price for the technology, but when there is overwhelming evidence of reducing mortality and cardiac arrests, for example, that’s the balance.”

Dealing with uptake

Why, then, has uptake not been more widespread? The usual arguments around the NHS’s size and structure will partly account for why these systems are not yet standard practice throughout hospitals – but so too is the way they have been implemented, argues Patience Chinwadzimba, nurse executive at Cerner.

It’s understandable if the rollout of a brand new system and way of working in a hospital is done slowly – but in her experience as a nurse, Chinwadzimba says this can cause more confusion and problems than it solves, and can lead to rollouts dragging out for years as other priorities take over.

“We would always recommend that instead of a rollout, if you have the equipment and resources, just do it in one big hit,” she says.

“When people have options, they choose the easier one and rollouts tend to take forever. It’s easier for nurses too, because when they go from ward to ward they are not going from electronic [systems] to paper.”

“When we see people tending towards a rollout, the perception is that we have more time to figure out if something goes wrong,” says Eneas Faleiros, a physician executive at Cerner.

“But our experience has shown that although the pain can be little bit higher [in a short rollout], the clinical risks and the focus that the institution has to get everything out suppresses all perceived risk from doing it at slower rate.”

The push for a paperless NHS is about more than just efficiency, argues Faleiros.

“It is not only about replacing paper, it is all the intelligence that an electronic system can add to the process,” he says.

“We see trusts driving discussions on the technological aspects and forgetting that it is also all about the patient, and we sometimes see a lack of communications on what the benefits could be.”

What’s next?

Just as the wider digital revolution is opening up exciting new vistas in almost every part of our lives, the potential of e-observations means its current iterations could be just the start.

Data, for example, has become one of the modern world’s hottest commodities – and electronic recording of patients’ vital signs generates reams of it. Nurses have entered patients’ vital signs into Nerve Centre’s system more than 50 million times, says Volkaerts – and that’s just one system.

The power of AI

Using powerful algorithms to scour this information for patterns will improve patient outcomes, something Kennedy from Patientrack describes as a “a second wave of value”.

“This data is used for research on things like sepsis or acute kidney injury, and that is much easier with digitised information,” he says.

“The deeper and higher quality the dataset, the more value that whole emerging area will be.”

As well as unearthing patterns from this growing mountain of data, artificial intelligence (AI) will also enhance electronic observations technology in other ways.

Natural-language processing, for example, through which machines can extract and digitise information from handwritten notes, could have tremendous time-saving benefits, says Kennedy, as could the advent of using voice-recognition systems – much like Amazon’s Alexa – for entering information.

“Ease of use is a real fundamental in anything used by healthcare professionals who are time-poor,” he says.

“The use of voice could find a strong place within these systems.”

Recognising human observation

As the digital automation juggernaut rolls on, however, it is vital not to forget the role played by subjective human observation, says Bloor from System C.

“These objective ways of measuring physiology are not a panacea,” he warns.

“As we get more sophisticated, some of the subjective measures become more important. People are saying we could become stupid if we rely on this stuff without engaging our brains as clinicians.

Those subjective things – a nurse or relative worried about a patient, for example – shouldn’t be forgotten.”

Reducing blue light submissions

Another next step in the evolution of this technology will be to take it out of hospitals altogether.

“It has been proven that early warning system save lives, so why wouldn’t we look at that technology for patients in the community with long-term conditions in order to reduce the need for blue light submissions?” asks Hopkins from Civica’s partner, Meditrack.

According to NHS figures, he adds, a patient over-65 who is admitted through the accident and emergency department faces an average hospital stay of more than nine days.

“That stay is taking up a bed for elective procedures – we can keep the patient in their home and reduce that burden.”

Bringing technology into patient’s homes

Enabling patients and their carers to monitor their vital signs at home and enter the data themselves will also benefit outpatients, says Cerner’s Chinwadzimba.

“Being able to monitor my own blood pressure and blood sugar at home, then post my results so my doctor can see how I am without me having to travel to hospital every time – there would be no buses to catch, for example, no more anxiety around that.”

Becoming more mobile

The growing spread and popularity of electronic observations systems might only be the vanguard of a wider movement towards single electronic patient record systems, argues Nervecentre’s Volkaerts, who believes the market will now consolidate towards using the latter; the former happened to come along at the same time as the mobile technology that has transformed all our lives, and this has been the key to its success.

“It’s not that electronic vital signs itself was the turning point – it happened to be a tool that was developed when mobile was becoming mainstream,” he says.

“The mobile tech is transformative, and vital signs is really just a use case. It’s just an app.”

And just as in wider society, as the digital revolution transforms our lives in ways we couldn’t have imagined even a few years ago, we will soon find how this technology will improve healthcare delivery – and we might still be surprised.

“We are on the cusp of some fantastic opportunities,” says Patientrack’s Kennedy.

22 July 2019 @ 09:58

No mention of the need to CE mark these. We have been informed by MHRA the NEWS would be a class I device.

16 July 2019 @ 10:20

Yes, application has been around more than a decade. It is good to see that vendors are adopting the technological changes. Technology can only be an enabler. It won’t add values unless it is adopted by the users. So it is important to learn the lessons from previous implementations and apply those lessons in the future implementations. For that partnership is required between application vendors and NHS Trusts. More outcome based white papers have to be published and vendors have to instil confidence to the clinicians and provide adequate support

It is interesting to see author’s point about rollout approach. It was quoted that NHS trusts preferred the rollout approach and few quotes about big bang adoption. Whether it is a phased rollout or big bang implementation, systems have to be configured, interfaces to be developed, tested and users to be trained before the rollout. For quicker deployment, both vendors and NHS trusts have to think and consider scaled agile framework. In addition to that it is important to ensure that patient safety is taken into care. As like any system implementation, stakeholder engagement is critical for successful system roll out. It can happen only with the support of CCIO, CNIO and digital champions.

Electronic observation and vital signs functionality is one of the core modules in e-Noting. By rolling out only this functionality, will not allow the trusts to achieve paperless state. Systems should allow clinical staff to capture Clinical notes, Assessment forms and Drs clerking electronically using open standards format.

The remaining hospitals will follow and deploy e-Noting systems at some point. It will be an interesting journey to transform the services and achieve the digital goals. This can only happen through partnership and support.

13 July 2019 @ 09:58

Great article. I’m a massive supporter of these technologies especially the mobile nature of these suppliers and the wider capabilities they bring beyond eObs.

On the point of evolving the technology for out of Hospital Care – would be interesting to see a Special report on what’s making this possible now.. asking patients to log resukts is nice – but not great.

Dartford & Gravesham have been utilising wearables to real-time capture patients VitalSigns where cared for at home, we’ve avoided blue lights, redirected patients to more appropriate services, detected AF via continuos monitoring, managed Oxygen requirements 24/7, been able to prioritise which patients are seen, and reduce home visits. Well be looking to further utilise this for in Hospital Monitoring of patients with a high news score is identified requiring frequent observations.

The technology is out there and can have significant impact. We just have to be brave enough to adapt and help companies pivot ideas and solutions to where they’re best needed.

12 July 2019 @ 12:14

Shame not to mention some of the research now supporting cNEWS – several excellent papers from Yorkshire looking at combining NEWS with blood results and the first NEWS linked to new computerised score calculated with age, sex, diastolic pressure and each parameter individually. Totally agree with comments about not removing the human element – nursing involvement with patient is still one of our best indicators of issues.