Making people wear seat belts saves lives, right? Well for drivers, yes – when seat belts are made compulsory death rates decline for those in cars.

But, sadly, drivers, feeling safer, drive that little bit faster and less carefully, snagging unfortunate warm bodies on the street as they go.

So mortality for cyclists and pedestrians rises, often cancelling out any overall gain. As is so often the case, a risk dealt with turns out to be a risk displaced to someone else.

Displacing risk

Risk is a fearsome driver of how the modern world works. It is what we spend much of our disposable income on avoiding – think bottled water, gated communities, gym membership.

And risk management is the negative incentive that drives much of the NHS. Nirvana in healthcare management is zero risk. Or, at least, zero risk that anyone can pin on me.

Risk management in this world quickly slithers into risk avoidance – being able to show that despite the disaster, all your own personal process boxes were neatly ticked. Not me Guv; must be those other guys over there.

For organisations, the dark side of risk management is exporting risk: the hospital manages the risk of breaching its waiting list target by cancelling appointments, so neatly transferring risk to patients.

Frontline staff collect reams of data that impedes their ability to care, but which helps someone manage risks higher in the food chain.

When I needed my ears syringing a few weeks ago, the trusty practice nurse who had done it many times before told me that because she had just been on an aural care course I had to make an appointment to have it done when a GP was in the building.

She was on her probationary period, so her next 20 aural consultations needed to be GP-supervised. Gold plated risk reduction for the writers of this protocol had been exported into multiple inconveniences for others down track.

Not to mention the marginal risk to me of not hearing one of those seat-belted car drivers bearing down on me.

Healthcare just is risky

The problem with all this, of course, is that medicine is an inherently risky business. Evidence is inadequate, priorities conflict, patients are individuals.

Great care doesn’t just mean being able to meld safe systematic care with individual circumstance. It means being able to bear the terrible responsibility of acting when there is no ‘best care’.

Sometimes, these are big judgement calls like initiating child protection, whistle blowing when you think a ward is unsafe, or informing HR that you think a colleague has an alcohol problem.

More often, it is about recognising that meeting organisational goals is less important than listening to the problem the patient has brought.

Or that the latest NICE guidance is derived from people with few co-morbidities who were seen in research settings, so following the resulting guidance is not necessarily mandated by God.

Professionals have a job to do

Ask yourself what it means to be a professional and you will find that the smaller, easier part of acting professionally is to implement the evidence, be systematic, and work well with colleagues.

The bigger, harder part is to ‘exercise discretion on behalf of another in the face of uncertainty’, to use a definition of professionalism that comes from Henry Mintzberg, a Canadian professor of management with a particular interest in healthcare.

In other words, the reason we pay professionals a lot of money is not primarily to do as we – or the evidence – tells them, but for them to exercise judgement amidst the storms of daily life where the evidence is ragged, certainty a distant shore, and nobody has a clue what to do.

For professionals to do this they have to savour risk; taste it. This means we have to applaud them when they handle tricky situations even if their judgement calls turn out – as they sometimes will – to be wrong. No one likes handling risk but pretending we can manage it out of existence does violence to reality.

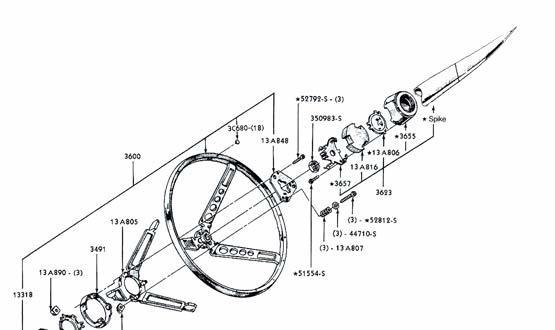

Adding spikes to steering wheels

To understand what this new attitude to risk might look like, let’s go back to the car driver snugly belted into her steel can.

Suppose car drivers had no seat belt and instead were confronted by a sharp spike pointing at them from the centre of the steering wheel. New incentives, huh? Slower, careful drivers, more happy pedestrians.

No more exporting risk, instead a driving career led in the full knowledge that how I act really matters to me and my fellow travellers on the road. Placing risk full and centre stage has different outcomes to trying to manage it or to export it.

So what might this look like for clinical practice? At is simplest it is a renewal each day of our commitment to offer up care that we would be happy for our own family to receive.

That’s a great ‘spike in the wheel’ but hard to keep in focus day in day out. Habitually asking ‘what did we learn?’ rather than ‘what went wrong?’ helps too, as does having a weekly celebration of how the team handled the tricky situations.

There is much that informatics could offer here. Suppose you could set your computer screen to display the face of someone close to you every time you were about to give someone bad news.

Or if the patient record automatically displayed how closely the patient sat in front of you resembled the research subjects on which guideline evidence was based. My guess is that all these would be effective spikes in the wheel.

Spikes for health

None of this means that we should junk the systems, protocols and checklists that the risk management culture is so good at creating.

After all, the spike in the driving wheel would probably be just as effective if the driver was in fact strapped in as well. Those seat belts really do help; it’s just that we need ways to celebrate the tougher aspects of what professionals do.

We need systems that reduce risk but that also encourage us to face the unavoidable quantum of risk that will always remain and to be valued by managers for doing so.

‘Risk management’ has become the glassy surface which encourages us to shuffle difficult issues off to others. It is the rationalisation by which we end up leading professional lives that are not true to ourselves.

By contrast, putting the risks we are responsible for centre stage, refusing to export them, living with them pointing at our heart day in, day out, is a celebration of the essence of being professional: of exercising discretion on behalf of another in the face of uncertainty.

Paul Hodgkin

Paul Hodgkin is chief executive of Patient Opinion, a website on which patients, service users, carers and staff can share their stories of care across the UK. Patient Opinion is a not-for-profit social enterprise based in Sheffield.

Until 2011 Paul also worked as a GP and has published widely including in the BMJ, British Journal of General Practice and the Guardian and the Independent. Follow him on Twitter @paulhodgkin.